You shouldn’t have to choose between the health of your heart and your bones. Yet, news headlines sparked by studies over the past decade have resulted in a lot of confusion about possible ties between getting too much calcium and an increased risk of heart attack. A new analysis in which scientists considered the evidence as a whole, however, provides reassurance: You can safely meet your calcium needs without putting your heart at risk.

Mei Chung, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in the department of public health at Tufts School of Medicine, and colleagues recently looked at the newest studies on calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk. “After reviewing and analyzing the research to date, we did not find strong evidence showing a relationship between calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk within the range of calcium amounts recommended by the National Academy of Medicine,” Chung says. Here’s a look at this evolving topic.

Tracing the Concern:

Nearly a decade ago, concerns about calcium and cardiovascular health were sparked by two reviews of clinical trials suggesting that people who took calcium supplements (with or without vitamin D) had about a 25% increased risk of heart attack compared to those given a placebo. “That worried a lot of physicians who had been recommending calcium supplements to patients at high risk for osteoporosis,” Chung says.

However, there were problems with that data. None of the trials used in those analyses were originally designed to look at the effect of calcium supplements on cardiovascular disease risk. So, some backtracking was needed. “To look at calcium supplements and cardiovascular disease risk, the researchers had to request unpublished trial data,” Chung explains. “That left the scientific community with a lot of questions about the quality of data that were used.” This approach also raised statistical questions about whether the observed effects of calcium supplements on heart attack risk were true or due to chance.

Weighing the Evidence:

To help clear the confusion, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) recently asked Chung and her team to review the latest evidence on calcium and cardiovascular health. In 2009, she and her colleagues at Tufts had conducted an extensive review on calcium and vitamin D that included research on cardiovascular disease risk. They found little evidence for concern. But, many studies have been published since then, so it was time for a focused update.

In the new review, they found that consuming calcium from food and/or supplements below the upper limits (amounts, above) of what previously has been deemed safe was not associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease or stroke. People in the studies typically didn’t consume more than the upper limits, so the cardiovascular effects of very high calcium intakes couldn’t be assessed.

Chung’s updated analysis included a review of 27 observational studies published up to mid-2016 that followed generally-healthy people for up to 30 years. The studies used surveys to determine how much calcium people consumed from food and supplements. Although not the primary purpose of the studies, heart- and/or stroke-related outcomes were also tracked. No consistent relationships between increasing amounts of calcium intake (from food and/or supplements) and cardiovascular disease or stroke risk were found.

Chung’s team also looked at four trials of calcium supplements (with or without vitamin D) on cardiovascular disease events and related deaths. These showed no significant differences in the risk of cardiovascular disease events or deaths between the groups receiving calcium supplements versus a placebo. Chung’s analysis is in Annals of Internal Medicine.

New Guidelines:

Using Chung’s analysis and other data, a separate group of experts representing the NOF and the ASPC put together clinical guidelines on calcium and cardiovascular disease to help guide practitioners. The guidelines state, “In light of the evidence available to date, calcium intake from food and supplements that does not exceed the tolerable upper level of intake (defined by the National Academy of Medicine as 2,000 to 2,500 milligrams per day) should be considered safe from a cardiovascular standpoint.”

The new guidelines say it’s preferred to get calcium from food sources. However, they also state, “Supplemental calcium can be safely used to correct any shortfalls in intake. Discontinuation of supplemental calcium for safety reasons is not necessary and may be harmful to bone health when intake from food is suboptimal.”

Supplement Concerns:

Despite the new guidelines, some practitioners are still concerned about possible harmful cardiovascular effects of calcium supplements (especially in high doses). Among those concerned is Erin D. Michos, MD, a cardiologist and the associate director of preventive cardiology at the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease in Baltimore, Maryland.

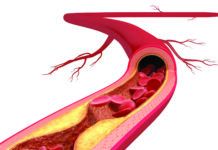

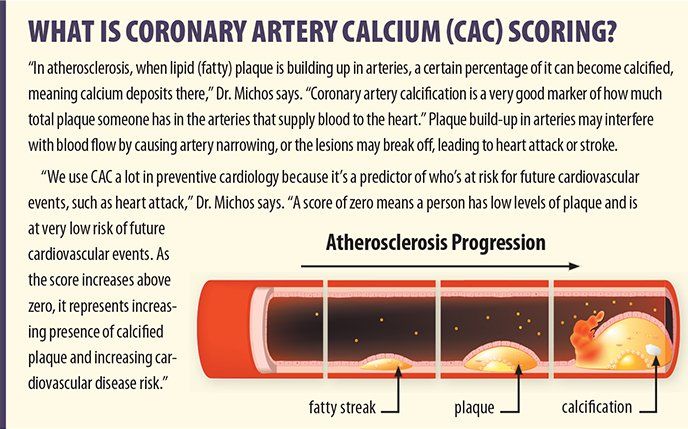

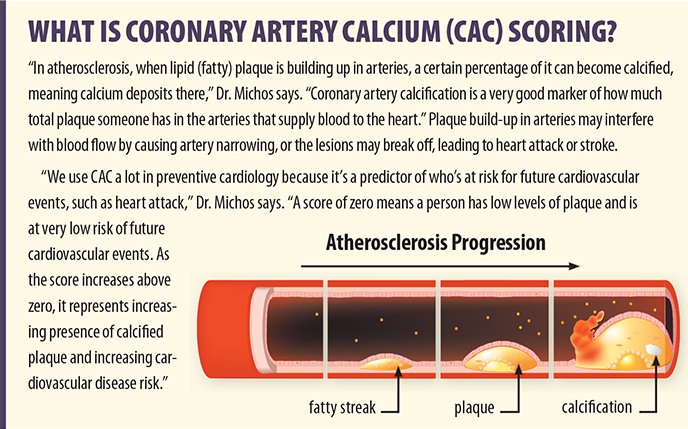

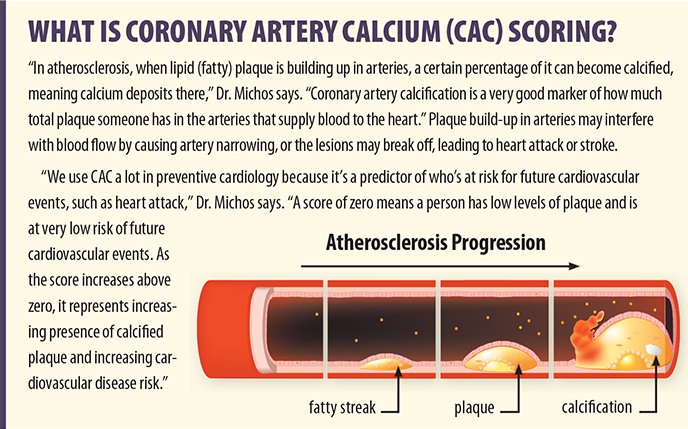

Dr. Michos and colleagues recently published an observational study of 2,742 adults (initially free of heart disease) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. The people, ages 45 to 84, had heart CT scans at the study start and 10 years later to compare changes in coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores (explained, below). These results were compared with the individuals’ calcium intake, collected from food surveys at the start of the study and by having people bring in their supplement bottles.

“Among people who started with a CAC score of zero, those who used calcium supplements were 22% more likely to have a CAC score over zero (suggesting progression of plaque build-up in heart arteries) at the 10-year follow-up, compared to those who didn’t take calcium supplements,” Dr. Michos says. “However, an increase in CAC score wasn’t observed with high calcium intake from food [defined by the highest quintile of 1,022 milligrams per day or more].” These results held true after adjusting for age, sex, exercise and multiple risk factors for heart disease.

Dr. Michos’ study wasn’t designed in a way that could prove the calcium supplements caused the changes in heart arteries. However, unlike previous studies looking at total calcium intake (from both food and supplements) and cardiovascular disease risk, this was the first one to compare the change in CAC scores over time and in a diverse group of people. Further study is needed.

Food Still Best Source:

We will likely see more research on calcium supplements and cardiovascular disease risk in the future, but trying to get most of your calcium from food is a safe bet. “If you take calcium in through food sources, you’re generally getting smaller amounts spread throughout the day (which is easier for your body to utilize) along with other nutrients that support bone health,” Dr. Michos says. “And, there have been no studies showing increased cardiovascular disease risk from eating healthful, calcium-rich foods.”

“There are so many good foods that have calcium, so I think most people can get close to their daily calcium requirement through food alone,” Dr. Michos says. “There will be cases where a calcium supplement is needed to help fill the gap between the calcium content of the diet and the daily requirement, but this should be decided in consultation with your doctor. And, there’s no evidence that getting more calcium – beyond your needs – is better.”

Tufts’ Chung also emphasizes that it’s best to get calcium from foods. “It would be difficult to regularly exceed the upper limit for calcium intake from foods, even if they’re fortified,” she says.

To learn more: Annals of Internal Medicine, December 2016

To learn more: Journal of the American Heart Association, October 2016