As the popular depiction of “leaky gut” goes, damage to the lining of the small intestine “can release undigested food particles, bacteria and toxins into your bloodstream.” And, that can potentially spur a myriad of health problems ranging from digestive issues to joint pain. Without a doubt, this description is oversimplified and misleading. But, it’s worth looking at whether leaky gut—or more precisely, increased intestinal permeability—is a legitimate concern.

“Several studies suggest an association between increased intestinal permeability and various human diseases,” says John Leung, MD, director of the Center for Food Related Diseases at Tufts Medical Center, assisted by his research intern, Khushboo Gala, MD. “But at this point, it’s not certain if increased intestinal permeability is a cause of these diseases or simply an associated finding.”

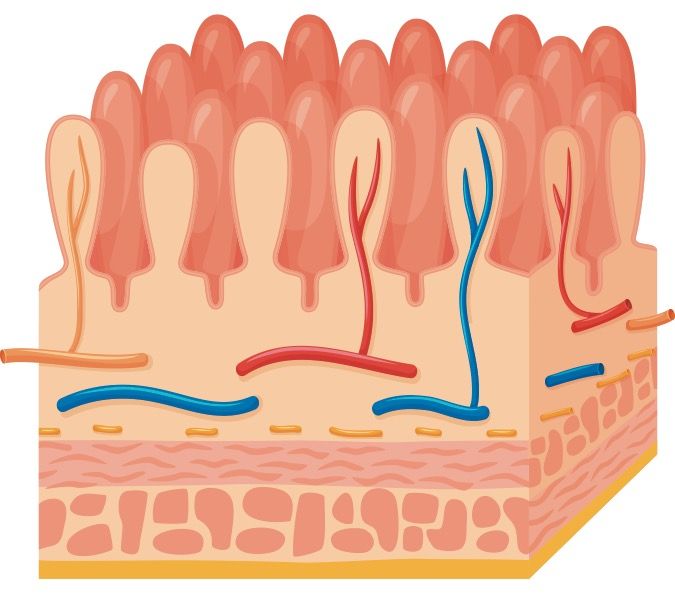

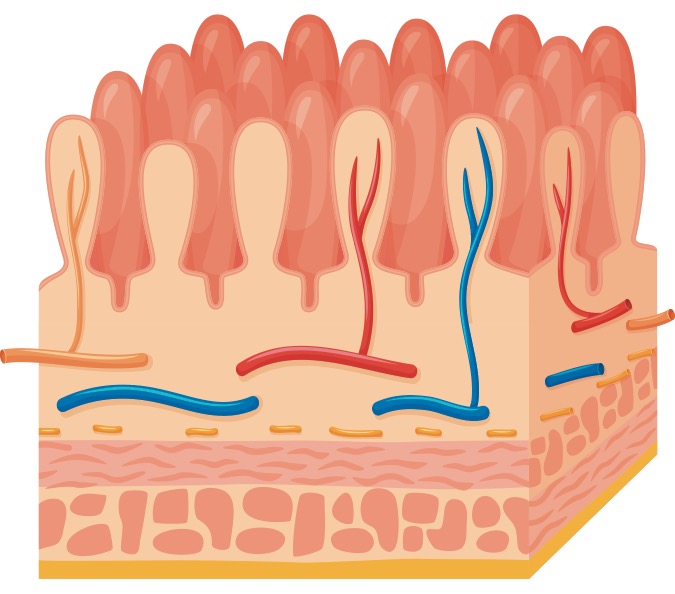

Gut Permeability: Although permeability of the gut can fluctuate, that doesn’t mean partially-digested pieces of food, like rice or corn, are circulating in our blood. “The gut lining is not like a spaghetti strainer with big holes in it,” says Joel Weinstock, MD, chief of the division of gastroenterology/hepatology at Tufts Medical Center. “If anything gets through that shouldn’t, it would be microscopic in size. And if a toxin gets into the bloodstream, the liver generally filters it out, before it can get into the circulation.”

One of the best-described ways (but, not the only way) that gut permeability can increase is when a person with celiac disease eats gluten (a protein in wheat, barley and rye). In response, the gut releases more zonulin. That’s a protein that helps regulate the junctions between the epithelial cells lining the inner wall of the small intestine. Increased zonulin activity in celiac disease allows gluten fragments through epithelial cell junctions of the gut’s inner wall.

“Until the discovery of zonulin, it was unclear how relatively large molecules like gluten fragments could get from the gut into underlying tissues,” says Alessio Fasano, MD, the founder and director of the Center for Celiac Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. He and his team discovered zonulin in 2000.

Past the Wall: “Many immune cells are just underneath the inner wall of the small intestine,” Fasano says. “When something unwelcome gets past the wall, the immune cells guarding the wall respond.” In celiac disease, the immune cells are triggered to attack the lining of the small intestine when they encounter gluten. And, activated immune cells could potentially travel to other parts of the body and cause inflammation and various symptoms, Fasano says.

The importance and causes of increased intestinal permeability observed in conditions beyond celiac disease (such as inflammatory bowel disease, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis) are unclear. “There is probably a subgroup of individuals with specific conditions in which increased intestinal permeability is more important than in other conditions,” Fasano says. “But, the viewpoint that fixing leaky gut will be the way to fix all diseases of humankind is an overstatement. Thetruth is likely somewhere in the middle.”

Best Advice: Tufts’ Leung and Gala caution people to be wary of practitioners (especially those without formal medical training) who claim to diagnose and treat leaky gut. Outside of research studies, there is no reliable, validated test to detect increased intestinal permeability.

They also caution against one-size-fits-all diets or treatments claimed to heal a leaky gut. Everyone is different. And, the science behind improving gut health (such as through changing our diet and gut bacteria) is in its infancy. “If you suspect you have a ‘leaky gut,’ see your doctor to get to the bottom of your symptoms,” Leung and Gala advise. Stay tuned for more research from Tufts and other groups on this evolving topic.

To learn more: Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, March 2016

To learn more: Tissue Barriers, October 2016

To learn more: Gastroenterology, November 2014

The villi (fingerlike projections of the small intestine important for nutrient absorption) are lined with epithelial cells. If the gut is leaky, unwelcome molecules can pass through gaps between the epithelial cells to the underlying gut tissue (the lamina propria). There, the molecules encounter immune cells and may set off an inflammatory reaction.