If a little is good, most Americans are accustomed to thinking, more must be better and a lot must be better still. When it comes to vitamins and minerals, however, it is possible to get too much of a good thing—especially if some of your nutrients are coming from pills instead of food.

“Remember that most of your vitamin and mineral needs can be safely met by a thoughtful diet,” cautions Irwin H. Rosenberg, MD, editor of the Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter. “The use of so-called ‘dietary supplements’ will always be associated with some degree of risk.”

Image: Thinkstock

Products marketed as “dietary supplements,” he points out, don’t have to adhere to the strict requirements for safety and effectiveness that govern medications. Under the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), manufacturers—not the FDA—certify that a product is safe. The FDA can take action only after a product reaches store shelves and a health hazard is detected. (See the June 2014 Special Supplement for more on such safety issues and how such products are regulated.)

Dr. Rosenberg adds, “It’s important to distinguish between vitamins and minerals versus other products also sold as ‘dietary supplements,’ such as herbal remedies, which don’t truly ‘supplement’ any proven nutrient need.”

According to the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institutes of Health <ods.od.nih.gov>, products sold as “dietary supplements” are most likely to cause side effects or harm when people take them instead of prescribed medicines or when people take many different products in combination. Some can increase the risk of bleeding or affect the response to anesthesia, and can interact with certain prescription drugs.

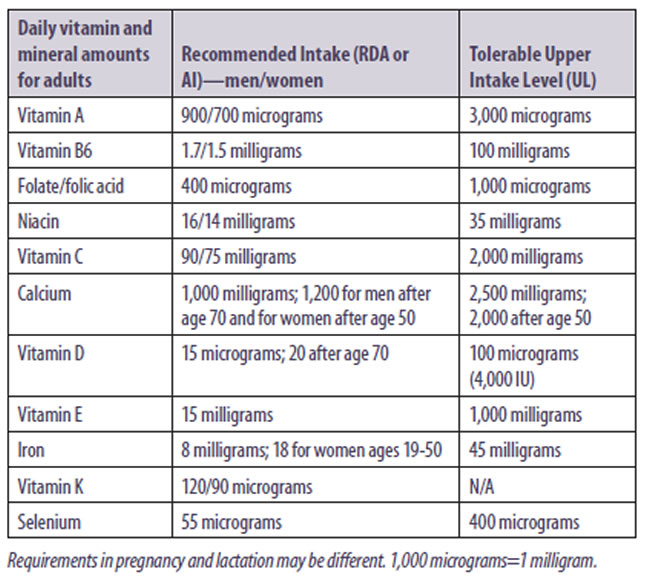

GETTING TOO MUCH: But with some nutrients there is also a risk simply in overdoing it. Fortified foods, including many breakfast cereals and some beverages, also contain some nutrients found in vitamin and mineral pills, including multivitamins, so you might be getting more than you think. The Institute of Medicine, which sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals, warns, “Like all chemical agents, nutrients can produce adverse health effects if intakes from any combination of food, water, nutrient supplements and pharmacologic agents are excessive.”

The Institute defines the tolerable upper intake level as “The highest level of nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects for almost all individuals in the general population.” As intake increases above the UL, the risk of adverse effects goes up as well.

The term “tolerable” is meant to connote a level of intake that can be tolerated biologically by individuals; it does not imply acceptability of that level in any other sense, the Institute cautions. The setting of a UL does not indicate that nutrient intakes greater than the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) or Adequate Intake (AI) but below the UL are recommended as being beneficial. Nor is the UL meant to apply to individuals being treated by prescription doses of that vitamin or mineral.

When considering possible risks from excessive intake of vitamins and minerals, it’s important to take into account all sources—including food, pills, fortified products and even “energy drinks.” Duration of intake is also a factor with minerals such as calcium or iron and the fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E and K; over time, these can accumulate in the body’s tissues and thus tend to have a greater risk of toxicity. While excess intake of certain water-soluble vitamins (B vitamins, vitamin C) can cause adverse effects, the body is able to excrete these and so they build up less in the tissues.

Here is a guide to the potential risks of the most important vitamins and minerals, according to the Office of Dietary Supplements:

Vitamin A: Toxic levels of vitamin A can cause headache, nausea, loss of appetite, dizziness, blurred vision, liver problems, birth defects and increased risk of fractures. People who drink high amounts of alcohol, those with liver conditions and individuals with unhealthy cholesterol levels are at greater risk.

Some multivitamin supplements contain high doses of vitamin A (also called retinol). Check the label to make sure that most of a multivitamin’s vitamin A is in the form of beta-carotene, which is not associated with toxicity, rather than as retinol or retinyl ester (types called “preformed” vitamin A).

B Vitamins: Most of the B-complex vitamins, being water soluble, pose little risk of overdose. As a result, ULs have not been established for thiamin, riboflavin, B12, pantothenic acid, biotin or choline.

Excess vitamin B6 can cause sensory neuropathy, a nerve condition that can lead to loss of control of bodily movements. It has also been associated with sensitivity to light, skin lesions, nausea and heartburn.

The risk of excess folate is primarily associated with its synthetic form, folic acid, used in pills as well as to fortify foods such as cereal and flour. High doses have been reported to increase the risk of certain cancers and, together with lower B12 status, to have central nervous system effects.

Even mildly high doses of niacin can cause flushing, headaches, itching and stomach problems. Large doses may trigger ulcers, gout, liver damage and other serious conditions.

Vitamin C: Although vitamin C has low toxicity, people who take too much may complain of gastrointestinal disorders due to the effects of unabsorbed vitamin C in the digestive tract. It has also been theorized that excess vitamin C may contribute to the formation of kidney stones, especially in patients already prone to oxalate stones. Another theoretical concern is that too much vitamin C could contribute to excess iron absorption.

Calcium: Here’s another reason to try to get most of your calcium intake from food, rather than pills: High intake from supplements, but not dietary sources, has been associated with increased risk of kidney stones. Some studies also link high calcium intake, especially from supplements, with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Too much calcium can cause constipation and may interfere with the absorption of iron and zinc.

Vitamin D: Most people need to worry about getting enough vitamin D, which the skin synthesizes from exposure to ultraviolet light (as in sunlight); if you’re not getting much sun, as in northern latitudes in winter months, it can be difficult to obtain adequate vitamin D from food alone. The adult UL for vitamin D, 100 micrograms daily, is equivalent to 4,000 International Units (IU)—two to four times the amount in high-dose supplements. You don’t have to worry about your body putting you over the limit due to sun exposure; that process is self-regulating.

Megadoses of vitamin D—well in excess of the UL—have been linked to weakness, appetite loss, cognitive issues, intestinal problems and long-term damage to soft tissues and kidneys. Since vitamin D is important for the body’s absorption and utilization of calcium, too much can also contribute to high blood calcium levels.

Another reason more is not better: Studies have shown that intakes of vitamin D above the UL do not further raise the blood levels of the vitamin.

Vitamin E: Getting lots of vitamin E from food is safe, but high doses in supplements have been associated with a risk of bleeding, including hemorrhagic stroke. Meta-analyses have also linked supplemental vitamin E, even at levels below the UL, with a small but statistically significant increased mortality risk. The SELECT study found that men taking 400 IU daily of vitamin E were at added risk of prostate cancer.

Iron: You’re unlikely to consume too much iron in your diet. Supplements in the form of pills or tonics, however, can lead to gastrointestinal problems and may compete with zinc absorption. High-dose iron pills (more than 30 milligrams) are a leading cause of accidental poisoning in young children.

People with a genetic condition called hemochromatosis suffer from an excessive buildup of iron in the body and should avoid iron supplements. Multivitamins formulated for older adults typically omit iron—check the label—because of the risk of iron overload.

Vitamin K: No UL has been set for vitamin K, but high doses can cause the breakdown of red blood cells and liver damage. People taking blood-thinning drugs or anticoagulants should regularize their intake of foods with vitamin K to avoid fluctuations, because of its blood-clotting effects.

Selenium: Too much selenium—a condition called selenosis—can cause gastrointestinal problems, skin rashes and lesions, hair and nail loss or brittleness, fatigue, irritability and nervous system abnormalities. Acute selenium toxicity can cause more serious adverse effects. The SELECT study found that men already with high selenium levels increased their prostate-cancer risk by taking supplements. In addition to high doses in pill form, Brazil nuts are very high in selenium (68-91 micrograms per nut).

Watch Tufts expert Dr. Irwin H. Rosenberg discuss dietary supplement safety. Click the link below.