We need to eat. Our bodies cannot function without the calories, nutrients, and fluids foods provide. But there are many other reasons we eat. We may, for example, be stressed, tired, bored, or simply around tasty foods. Often, these non-physiological triggers involve cravings. “Hunger is the body’s way of telling us to eat in order to maintain our energy levels,” says Tammy Scott, PhD, a research and clinical neuropsychologist who serves as a research assistant professor at the Friedman School. “Food cravings can occur even when we’re not hungry.” Cravings can be tough to ignore, but there are steps you can take to address them.

What is a Craving? A craving is a powerful desire for something. You may crave a particular food when you’re hungry, but food cravings often occur without biological hunger. Psychologists recognize two basic kinds of craving: cue-induced and tonic. Cue-induced cravings, as the name suggests, are triggered by something in the environment. You may desire a particular food after seeing a commercial for it, long for a burger when the smell of grilling wafts past you in the air, or want to eat the whole bag after tasting one chip. Tonic cravings are not a reaction to environmental stimuli. They may be frequent and recurrent and are typically related to deprivation. For example, if you are trying to avoid sweets, you may find yourself longing for them.

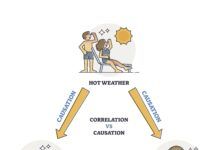

The Cause(s). Many factors can contribute to food (and beverage) cravings. Internal cues—things our own bodies tell us—are one common culprit. “The neurobiology behind cravings is complex,” says Scott. “In some people, eating highly palatable foods—usually those that are enjoyably rich and sweet or salty—activates the brain’s reward centers, creating feelings of pleasure. These foods may also trigger the release of hormones that reduce feelings of stress. These positive feelings may motivate us to seek out these foods more often, which can lead to poor dietary choices.”

Research suggests both positive emotions (like happiness) and negative ones (like sadness or anxiety) play an important role in our desire to eat, but not everyone responds the same way. For example, some research has shown people who are restricting their food intake are more likely to be prone to emotional eating. In fact, following restrictive “diets” often increases the likelihood of cravings in general—we tend to desire what we can’t have.

While some people eat more when they’re stressed, others eat less or the same amount as always. Stress can cause the body to call for more calories to meet the ancient need to “fight or flee.” Like stress, fatigue from lack of sleep may cause the body to seek out extra (likely unneeded) energy from food.

➧ Hungry? Go ahead and have some fruit, a handful of nuts, or some fat free or low-fat yogurt. ➧ Tired? Grab a quick nap and work on getting at least seven hours of sleep a night. ➧ Stressed? Try a walk, some deep breathing, yoga, or meditation instead of food. ➧ Sad? Seek help and support. ➧ On medication? Certain medications, including steroids, anti-seizure drugs, certain antidepressants, and oral contraceptives can increase hunger. Talk to your healthcare provider about possible alternatives. ➧ Dieting? “Avoid severely restrictive diets,” says Scott. “People who completely cut out all carbs, for example, are more likely to crave them.” ➧ Tempted? Keep your personal trigger foods out of the house (and put a bowl of fruit on the counter instead). If you can’t resist the Siren call of the drive-thru on the way home from work, take a different route! ➧ Thirsty? It can be hard to tell the difference between thirst and hunger. When you crave a snack, drink a glass of water or seltzer first and see if the craving subsides.

What to Do. If you find cravings are sabotaging your efforts to make healthy dietary choices or are causing you to overeat, there are steps you can take to help quiet them. “I start by providing my clients with education on the differences between head hunger and physical hunger,” says Haijia Liu, LICSW, a behavioral health clinician at the Weight and Wellness Center of Tufts Medical Center. “It is possible to improve one’s awareness of what is behind a desire to eat.” See the Take Charge! box for some tips.

“For many people, hunger and satiety cues can be skewed,” says Liu. “This can make it difficult for them to discern head hunger from physical hunger. I have found working on eating regularly and getting proper nutrition can help my clients better read their internal cues.”

In the moment, Scott recommends distraction. “If you’re having a craving, try taking a walk or listening to a favorite podcast.” Even if you later act on the craving, this tactic can still be helpful. “I typically encourage clients to work on delaying acting on the cravings for even a few minutes,” says Liu. “Compared with acting on the urges automatically, delaying is already a victory. Over time, clients will hopefully be able to wait for longer and longer periods of time and eventually ride out the waves.”