“It’s remarkable what happens to food after you’ve swallowed it,” says Andrew Plaut, MD, gastroenterologist at Tufts Medical Center and author of Know Your Gut: Straight Talk on Digestive Problems from a Gastrointestinal Physician. “Your digestive system knows what to do with everything you send its way, from whole grains and vegetables to bagels or pretzels. Each nutrient, whether fat, starch, protein, mineral or vitamin, is handled differently and absorbed by different mechanisms.”

The Gastrointestinal Tract. The GI tract is considered “outside” our body—a tube, from the mouth to the anus, with a lining that separates the inside of our body from the food we eat. The GI tract determines what is absorbed into our body and which nutrients enter the bloodstream to be shipped to where they are needed.

- Fill Up on Fiber. Eat plenty of fiber-rich foods, like fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, and whole grains. This is a great way to keep the contents of your GI tract moving. Fiber also nurtures a healthy gut microbiota.

- Care for Your Liver. Eat a healthy diet, engage in regular physical activity, avoid processed starches and sugars, and try to lose excess weight to protect against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Avoid excessive consumption of alcohol.

- Don’t Stress Your Pancreas. Help your pancreas control blood sugar levels by eating healthy, minimally processed foods, being physically active regularly, and maintaining a healthy weight.

- Get Checked Out. Report chronic heartburn, belly pain, changes in bowel habits, and any other gastrointestinal concerns to your healthcare provider, and get a colonoscopy at least every 10 years if you are over 50 years old (or sooner if you have a family history of colon cancer).

Plaut likens the GI tract to a slow-moving river. “The contents of the whole gut is dependent on motility, moving with muscles and nerves in a highly coordinated structure,” he explains. This movement, not too fast, not too slow, is essential to a well-functioning digestive system.

Various types of food processes, for example grinding, heating, and hydrating, can change nutrient availability and how that food behaves in the GI system.

Mouth. The amazing journey we call digestion begins even before we put food into our mouths. Just the smell or sight (and sometimes thought) of food stimulates the secretion of saliva, making our mouths water. The first bites signal the production of increased secretion of saliva, which begins to break down starches with the enzyme salivary amylase as your teeth tear and grind the food into smaller, more digestible pieces. The food is moistened and lubricated so that it can be comfortably swallowed. Swallowing occurs in the throat (pharynx), which sends the food to the esophagus.

Esophagus. The esophagus is a muscular tube about 10 to 13 inches long that connects the throat to the stomach. With each swallow, a valve in the upper part of the esophagus opens, allowing masticated food and liquid to enter. The mass of chewed food is then pushed downward by muscle contractions toward the lower esophageal valve, which opens to let the pieces of chewed food and liquid pass into the stomach.

Stomach. The stomach breaks down food further and holds it until it’s ready to be sent to the small intestine. It expands when full and shrinks when empty. When your meal enters the stomach from the esophagus, it signals the release of gastric acid, which activates digestive enzymes to begin the breakdown of proteins. (Gastric acid also helps protect us from foodborne illness by destroying unwanted organisms.)

The stomach muscles contract and relax to mix the enzymes and acids with the food you just ate. This end result is a mixture the consistency of a diluted paste.

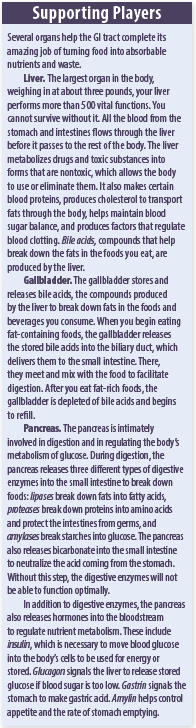

Small Intestine. The stomach contents moves into the small intestine, where it will be broken down even further. This is where most nutrients are absorbed, including proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and micronutrients. About 20 feet long and one inch in diameter, this coiled tube is connected to the stomach on one end and the large intestine, also known as the colon, on the other. The first section of the small intestine (the duodenum) completes the digestion phase, using enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the gallbladder to break down the food (see Supporting Players). The food then moves into the middle section (the jejunum) where the bulk of nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream. The third and final section (the ileum) is where the last of the absorbable products of digestion, including bile acids and vitamin B12, are taken in to the body.

Large Intestine. Anything not yet digested and absorbed moves on to the large intestine, or colon. This material most commonly includes dietary fiber from fruits, veggies, beans, whole grains, and nuts. The large intestine is a muscular tube that is three times wider than the small intestine but only about five feet long. From where it meets the small intestine, the colon wraps up the right side of the body, across the top just below the ribcage, and down the left side, where it connects to the rectum. The remnants of digested food as well as unabsorbed fluids and dead cells from the lining of the intestines enter the large intestine as a slurry. The large intestine absorbs most of the water, changing the waste from liquid to solid. The resulting stool is then stored until it’s emptied into the rectum. It typically takes about 36 hours for stool to pass through the large intestine.

A complex organization of bacteria in the large intestine (commonly called the “gut microbiota”) feed on material such as fiber, producing beneficial compounds (and sometimes harmful ones) that can impact our health. Keeping these important bacteria healthy and well-fed with plenty of fiber is important for our health.

In addition to housing these important microorganisms, the gut produces many hormones and is a major part of our immune system. “We don’t yet fully understand all the important roles the GI tract plays beyond digestion,” says Plaut.

In the “Take charge” section, it states “Avoid excessive consumption of alcohol.” How much is excessive? Is any amount safe? Many health professionals consider it a toxin.