For ideal health and physical well-being, it’s recommended each week adults aim to do a total of two-and-a-half hours of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity). Even if you don’t meet this physical activity target, considerable research has demonstrated any activity is better than none.

Why Move More? “We are beginning to understand that being sedentary (spending a lot of time sitting or lying down) is dangerous in itself,” says Roger Fielding, PhD, senior scientist and director of the Nutrition, Exercise Physiology, and Sarcopenia Team at the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University. “Data show sedentary behavior is associated with increased risk of obesity, cardiometabolic diseases (heart attack, stroke, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels), cognitive decline, and probably certain cancers, such as bladder, breast, colon, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, lung, stomach and maybe prostate.”

In a recent study, which followed nearly 106,000 adults from 21 countries for eight to 12 years, researchers found that high amounts of sitting time were associated with risk of death from any cause. Compared with those who sat less than four hours a day and reported a high physical activity level, participants who sat for eight or more hours a day experienced a 17 to 50 percent higher associated risk of death during the study period, depending on how physically active they were (risk decreased as physical activity levels increased).

Sedentary behavior was also associated with higher risk for cardiovascular events, including heart attack, stroke, and heart failure.

One study found that even otherwise sedentary individuals could reduce their risk of premature death with as little as 30 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity a day. Analysis of a representative national health survey concluded an estimated 110,000 deaths a year could be prevented if U.S. adults ages 40 and older increased their moderate-to-vigorous physical activity by as little as 10 minutes a day.

Aerobic activity (getting one’s heart rate up) is known to be good for cardiovascular health, but even non-aerobic physical activity is associated with lower risk for type 2 diabetes and falls, less fatigue, and decreased risk of developing some types of cancer, and it may help cancer survivors live longer.

“We know a programmed exercise/workout routine, such as going to the gym for a 30-minute class, certainly has benefits,” says Fielding, “but we are developing a deeper appreciation for the idea that even small amounts of physical activity—things you do around the house or in your yard—all count. They may not be ‘exercise’ per se, but that type of physical activity matters when you talk about the health benefits of moving more.” These activities include things like housework, gardening, running errands, and shopping for groceries.

Exercise vs. Physical Activity. “The term ‘exercise’ implies a regular, repetitive, often prescription-driven approach to activity,” says Naomi Lynn Gerber, MD, professor emerita at George Mason University and director for Research, Medicine Service Line at Inova Health System. “Physical activity can include exercise, but it is also related to functional and purposeful participation in daily life.” Fielding agrees. “Years ago, we thought about exercise as a prescription,” he says. “We wanted to formalize it and make it like a medical treatment. But this doesn’t work for everyone, and the prescriptive nature of exercise became a barrier for some.”

“Recent data support the view that leisure activity is as effective as prescription exercise in reducing risk for cancer and recurrence of cancer, and in reducing all-cause mortality,” says Gerber. “In my specific area of research—non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity—we have a great deal of data that increasing activity (not necessarily exercise) helps mobilize fat from the liver and improves the metabolic profile.”

A study of sedentary adults at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes found that simply spending more time standing, rather than sitting, was associated with better insulin sensitivity. In the LIFE (Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders) study, in which Fielding took part, researchers found what is known as a dose-response effect. “The more active participants were, the more health benefits we saw,” says Fielding, “but we found even a small increase in physical activity led to a reduction in disability.”

“These small amounts of activity are not likely to improve aerobic capacity,” says Gerber, “but the functional and preventative benefits that accrue from even very minimal activity can be quite significant.”

- Stand Up. Take a standing break every hour or half-hour if you sit a lot. Raise your work surface to create a standing desk.

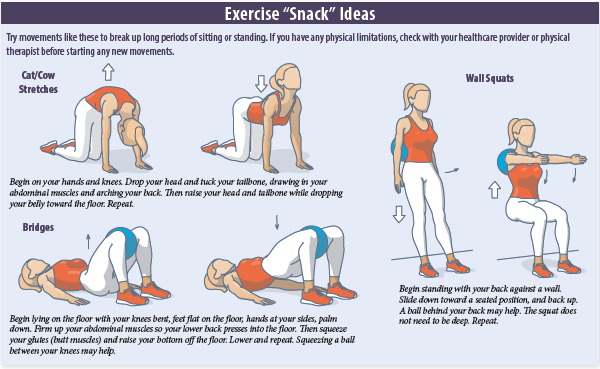

- Take “Snack” Breaks. Do eight to 10 wall squats periodically if you stand a lot; practice balancing on each foot for 10 seconds a few times a day, see how many times you can rise from your chair and sit back down in 30 seconds; raise your arms above your head seven or eight times to counteract the effects of time at a computer or writing.

- Walk. Around the block, around a track, up and down the stairs, or in an indoor mall, supermarket, or office building.

- Work at Home. Vacuum, mop, dust, garden, shovel, wipe, and sweep.

- Play. Dance, ride a bike, swim, bowl, play tennis, pickleball, ping pong or another sport.

- “Exercise.” Jog; practice yoga or tai chi; use a treadmill or stationary bike, take part in a fitness class; lift weights.

- Get Creative. Get up and move around during commercials or between episodes of streaming shows; park further from the office or stores; take the stairs, not the elevator or escalator; walk around the block when you get the mail; walk or bike short distances rather than driving; get off the bus one stop early or one stop later; carry grocery bags to the car without a cart.

“It is key to avoid maintaining fixed postural positions.” says Gerber. “This includes both sitting or standing for long periods of time.” Gerber recommends interrupting these fixed positions with periodic ‘snacks,’ like standing up and sitting down as many times as you can in 30 seconds. “This sit-to-stand exercise helps improve long term function and reduces likelihood of falls,” she explains. If you stand for more than an hour at a time, Gerber recommends ‘snacks’ like wall squats (see image); lying on your back and bringing your knees to your chest; bridges (see image); and cat/cow stretches (see image).

Another important ‘snack’ for those who spend a lot of time sitting is balancing on one leg at a time. In a study of over 1,700 participants ages 51 to 75, participants who could not hold a one-legged stance for 10 seconds had nearly twice the risk of death over the next seven years. Balance is critical to preventing falls, which are a major cause of injuries and impact one third of the population 65 and older each year.

“These activities are not going to increase strength or improve aerobic capacity,” Gerber explains, “but they will help break up fixed postures, relieve muscle stiffness, and increase back mobility and balance. These are all important for good function.”

“If you want to be able to run, swim, and cycle as you age, you’ll need to engage in more strength training and aerobic activity,” says Fielding, “but the benefits of even small amounts of physical activity are significant.”