Protein is getting a lot of attention these days. High-protein diets are all the rage, protein supplement sales are booming, and protein is being added to everything from breakfast cereals and snack bars to pastas and smoothies. But most people don’t need all that extra protein, and there could be some downsides to overdoing it. Most Americans already get more than the recommended amount of dietary protein, and, in most cases, research does not support getting more.

Q. How much protein do I actually need?

A. The actual amount of dietary protein your body needs depends on a number of factors, including your size, age, sex, activity level, and health status.

In the U.S., the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day (g/kg/d). To determine your recommended grams of protein in pounds, multiply your weight in pounds by 0.36. This comes to roughly 54 grams of protein a day for someone who weighs 150 pounds, and about 72 grams for a 200-pound person. (See Are You Getting the Right Amount of Protein? on page 4 for more information.)

Q. Should I try to get more protein?

A. “We tend to consume more than enough protein already,” says Roger A. Fielding, PhD, director of the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) Nutrition, Exercise Physiology and Sarcopenia Laboratory. According to a national survey, 85 percent of Americans meet or exceed the recommended amount of protein. One study found the majority of U.S. adults eat somewhere around 1.0 to 1.5 g/kg/d, well above the recommended 0.8 g/kg/d.

There are some circumstances where this extra protein may be warranted:

Building Muscle: While simply increasing protein intake has not been shown to build muscle, it may help increase muscle strength when combined with a program of regular muscle-building exercise. “During aerobic or strength training activities, protein turnover increases,” Fielding explains. “In other words, your body may break down more protein than it is making. An abundance of evidence suggests people who are physically active probably require more dietary protein per day—up to 1.1 g/kg—to make up the difference. But keep in mind, most people in the U.S. already consume at least this much protein.”

Aging: Some studies suggest older adults could benefit from getting a bit more than the RDA for protein, but the jury is still out. “As we age, we lose muscle mass,” says Fielding. “If an older adult is eating a low protein diet or not consuming protein throughout the day, muscle loss may be accelerated.” In a number of studies, high-protein interventions

did not help maintain muscle mass in adults aged 65 or older who already consumed adequate amounts of protein at baseline. However, other studies, including a long-term study led by Tufts researchers, found higher protein intake across adulthood was associated with significantly lower risk of losing physical function with age, particularly in women.

While the U.S. RDA for protein is 0.8 g/kg/d (0.36 g/lb) for adults of all ages, some international expert groups recommend a protein intake of 1.0 to 1.2 g/kg/d for adults over 65 years old. The participants in the Tufts’ study were averaging protein intake of 1.0 g/kg/d, indicating most older adults in the U.S. don’t necessarily need to change their eating habits to meet this higher intake goal.

Weight Management: If you are cutting calories to lose weight, be careful to keep your intake of protein foods at the recommended level. “When people cut calories across the board, they generally cut protein intake along with carbohydrates and fats,” says Fielding. “If the body is not getting enough dietary amino acids to build all the proteins it needs, it will break down muscle tissue to get to the amino acids stored there. These dieters will lose body fat, but also lean mass (muscle).” Making sure a higher percentage of calories on a low-calorie diet comes from protein can help.

Image © wetcake | Getty Images

Q. Does it matter what source my protein comes from?

A. While most U.S. adults get plenty of protein in their diets, the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend shifting the food sources of proteins we consume for optimal health. For example, while average intake of total protein foods is at or above recommendations, average seafood intake is below recommendations. Intake of legumes is also low.

“Any protein source will meet one’s protein needs,” says Mozaffarian, “so it’s what comes with the protein that matters.” A low-sodium food, for example, is a healthier source of protein than a saltier option, and a plant protein source, which also provides fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, is a better choice than a slice of bologna. For optimal health, replace red and especially processed meat (deli meats, bacon, sausage, hot dogs, ham) with seafood and beans, nuts, and other plant sources of protein. Eggs, poultry, and dairy products (or fortified soy alternatives) in moderation are also good alternatives to red and processed meats.

Protein from healthy food sources is overall preferable to supplements: it is safer than unregulated dietary supplements, contains multiple naturally occurring nutrients, and is generally cheaper.

Image © wetcake | Getty Images

Q. If I’m shifting to less meat and more plant foods, how can I be sure I’m getting adequate protein?

A. All proteins are built from just 20 amino acids. The body can manufacture 11 of these, leaving just nine that we have to get from food. These “essential” amino acids are found in animal foods (meats, poultry, fish/seafood, dairy, eggs) as well as in plant foods (particularly legumes, nuts, seeds, and some grains). Animal foods contain all nine of the essential amino acids (what used to be called “complete” proteins). Some plant foods contain all nine (for instance, soy, quinoa, chia seeds, and buckwheat), but most other plant foods are low in at least one of the essential amino acids (sometimes referred to as “incomplete” proteins).Health and nutrition experts recommend eating more plant foods and less animal products. This will not create a problem with protein intake. In fact, it is possible to meet all protein needs without eating any animal products at all, as long as you eat a varied diet that includes all kinds of plant proteins, including legumes, whole grains, and nuts/seeds.

While it used to be thought that “incomplete” plant proteins needed to be combined at each meal to create a complete protein source, it is now understood that meeting all essential amino acid requirements within a single day is sufficient. “Given the variety of plant foods available in the modern diet, no one really needs to worry about matching different plant sources of protein,” says Mozaffarian, “unless their diet is very regimented and limited to just a few specific plants.” Still, complete combinations of plant proteins have evolved over time in every culture, including rice and beans, pita and hummus, and even peanut butter on bread.

Replacing some animal proteins with plant proteins is not only associated with positive health outcomes, it’s a better choice for the environment. Red meat production in particular requires large amounts of water and energy and creates high levels of greenhouse gas emissions. “Some meat-eaters are choosing to decrease their intake, frequently for multiple reasons: the environment, sustainability, or health,” says Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, director of the Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory at the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging and executive editor of Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter. “In response, the market for plant-based meat substitutes is booming. While in some ways these products are better for the environment, be aware that they are highly processed and may have a nutrient profile not all that dissimilar to meat (including added saturated fat) and may be even higher in sodium.” Plant-based “meats” can be useful options, but swapping red meat for legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains is a better way to cut back on red meat intake, improve diet quality, and help the environment.

Q. When is the best time of the day to consume protein?

A. The latest research indicates protein intake should be spread out throughout the day for optimal health. “Protein synthesis occurs in your body all day long,” Fielding explains, “If you only consume protein in one meal, you’re missing an opportunity to optimize protein synthesis, and also to build muscle.” The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend people who choose to eat animal sources of protein reduce portions at dinner to around three ounces and including more protein at breakfast (see What to do About Breakfast on page 1 of this month’s Newsletter for breakfast ideas). If you’re adding a protein-rich food to a meal, substitute it for something else you’d normally eat (rather than eating it in addition to what you’d typically eat).

Another reason for spreading out protein intake is that the body can only make use of a limited amount of protein at a time. Studies suggest consuming no more than 20 to 25 grams of protein at once.

Image © JulijaDmitrijeva | Getty Images

Q. Is it possible to consume too much protein? Can it do any harm?

A. Around 65 percent of adults in the U.S. report they are trying to eat more protein, and high-protein diets have exploded in popularity in recent years. Unfortunately, many high-protein diets tend to be low in plant foods and rely heavily on animal products. Such a dietary pattern can be high in sodium, saturated fats, and heme iron, and low in healthy foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes and healthy plant oils. There are some health concerns associated with very high protein intake.

Type 2 diabetes: “Population studies show high protein intake may be associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes,” says Mozaffarian. “While mechanisms are not clear, excessive dietary protein could stress the pancreas and insulin secretion long-term. Other ingredients in high animal-protein diets, like too much heme iron from red meats, could also be causing harm.” (Other factors associated with dietary patterns high in protein may also contribute to higher diabetes risk and can’t be ruled out.) Replacing some animal protein with plant protein was associated with a protective effect in some studies.

Kidney function: Protein influences how hard the kidneys work. While current data seem to indicate healthy kidneys can handle excess protein intake, for people with reduced kidney function, sticking to the recommended 0.8 g/kg/d (0.36 g/lb) could slow kidney function decline. If you are uncertain about how much protein to consume, discuss the matter with your healthcare provider.

Bone Health: “There is no question that meeting the recommended protein intake of 0.8g/kg/d is important for bone health,” says Bess Dawson-Hughes, MD, director of the Bone Metabolism Laboratory at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, “but high intake of protein combined with low intake of fruits and vegetables may cause a problem for our bones.” Breakdown of amino acids after absorption can create sulfuric acid, Dawson-Hughes explains. The body neutralizes this acid by drawing calcium from the bones, so too much protein could actually end up weakening bones. Vegetables and fruits (even acidic fruits like citrus) add acid-neutralizing compounds to the body when they are broken down. Emerging research by Dawson-Hughes and her colleagues at Tufts suggests following standard dietary guidelines—in line with diets such as the DASH diet or a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern—provides the ideal acid-base balance for bone health. For most Americans this means more fruits and vegetables, less grains (especially refined grains), and protein in line with recommendations.

Microbiome: Some research suggests protein intake in excess of requirements could be bad for the gut microbiota—particularly those microorganisms that are thought to be beneficial to our overall health.

- Calculate your protein needs. Multiply your weight in pounds by 0.36. This is your Recommended Dietary Allowance for protein (equivalent to 0.8

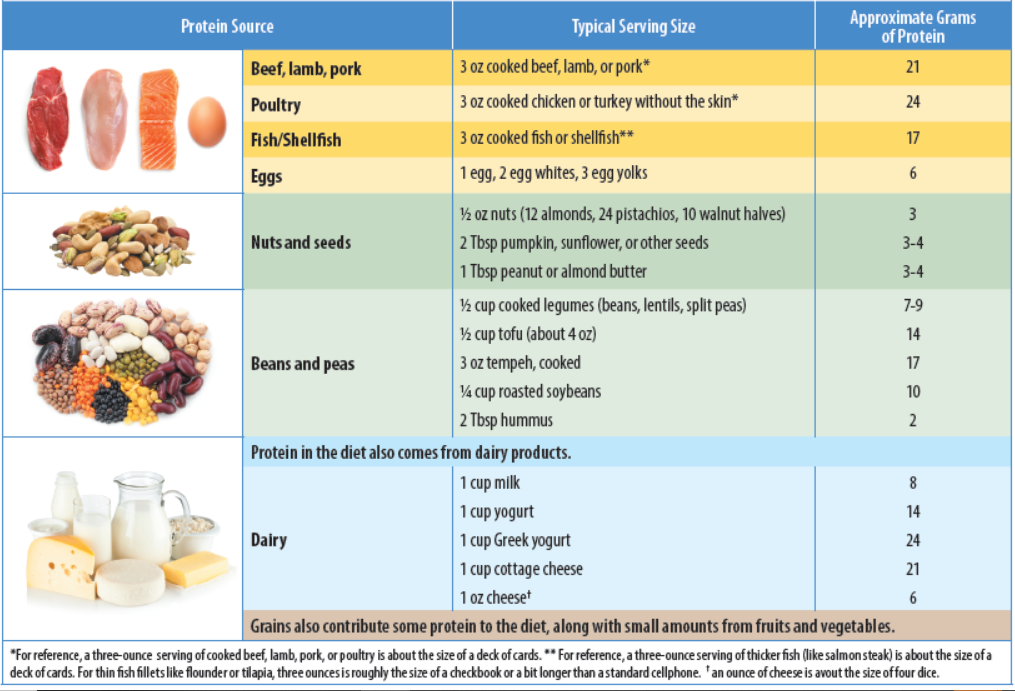

g/kg/day). [Note: People who regularly engage in muscle-building exercises may benefit from protein intake at or around 0.45 grams per pound (equivalent to 1.0 g/kg/day). Some experts support protein intake at this level for people over 65 as well. But keep in mind most Americans already meet this higher goal.] - Use the chart below to get an idea of what combinations of foods you can use to meet your protein needs. Remember to choose fish, legumes, nuts/seeds, or other plant sources more often in place of red and processed meats, and to spread your protein intake out throughout the day.