Two of the nation’s leading nutrition experts have some advice for the federal government: Stop worrying about total fat. Nutrition research has shown that the emphasis on restricting total fat intake is outdated, yet these limits affect everything from Nutrition Facts labels to school lunches to supermarket products. In recent opinion pieces in JAMA and the New York Times, Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH, and David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD, argue, “It’s long past time for us to exonerate dietary fat.”

Dr. Mozaffarian is dean of Tufts’ Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and editor-in-chief of the Tufts Health and Nutrition Letter. Dr. Ludwig is on the staff of Boston Children’s Hospital and directs the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center.

However the federal government responds to this call for change—in the upcoming 2015 US Dietary Guidelines, revised nutrition labeling and other policies—you can catch up with the latest nutrition science in your own grocery shopping and food preparation right now. If, like Uncle Sam, you’re still worrying about the total fat numbers and calories from fat on the Nutrition Facts panel, it’s time to take a more nuanced view. If you’re avoiding foods high in healthy unsaturated fats, you need to rethink your fear of fats.

DATED NUMBERS: The 2015 report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) drew headlines for overturning most concerns about consumption of dietary cholesterol, as in eggs (see the May newsletter). Tufts faculty members Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, and Miriam Nelson, PhD, served on the committee, and Lichtenstein was vice-chair. As Dr. Mozaffarian and Dr. Ludwig point out, however, “A less noticed, but more important, change was the absence of an upper limit on total fat consumption.”

Noting that reducing total fat intake by substituting carbohydrates does not reduce cardiovascular risk, the DGAC concluded, “Dietary advice should put the emphasis on optimizing types of dietary fat and not reducing total fat.”

That recommendation, if reflected in the final guidelines due later this year, would reverse 35 years of nutrition policy. In 1980, the federal Dietary Guidelines first recommended limiting dietary fat to less than 30% of calories. Since one gram of fat—regardless of the type of fat—contains about 9 calories, in a 2,000-calorie daily diet that advice translated to a maximum of 65 grams of fat per day. The 1980 recommendation was revised in the 2005 guidelines to a range of 20% to 35% of calories from total fat. But the percentages used in the Nutrition Facts panel continue to be based on the 1980 recommendation of 30% or 65 grams.

SUBSTITUTING CARBS: Fat is a concentrated source of calories—that 9 calories per gram of fat compares to 4 per gram of protein or carbohydrate. So limiting fat intake seemed like a sound strategy for preventing obesity. As the Times op-ed recounts, “By the mid-1990s, a flood of low-fat products entered the food supply: nonfat salad dressing, baked potato chips, low-fat sweetened milk and yogurt and low-fat processed turkey and bologna. Take fat-free Snackwell’s cookies. In 1994, only two years after being introduced, Snackwell’s skyrocketed to become America’s No. 1 cookie, displacing Oreos, a favorite for more than 80 years.”

In place of fat, Americans were advised to eat carbohydrates, which were positioned as the foundation of a healthy diet. In 1992, the USDA’s famous “food pyramid” recommended up to 11 daily servings of bread, cereal, rice and pasta. (By contrast, the current MyPlate nutrition icon recommends women consume five to six ounces or ounce-equivalents of grains, depending on their age, and six to eight for men. At least half those servings should be whole grains.)

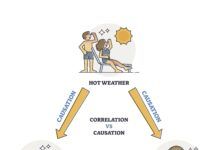

Replacing fats with carbohydrates, especially refined sources as in packaged foods, backfired as an anti-obesity strategy. Between 1980 and 2000, obesity rates among US adults doubled.

In the thinking behind the 1980 total-fat limit, saturated fat was also linked to unhealthy cholesterol levels. “But the campaign against saturated fat quickly generalized to include all dietary fat,” Dr. Mozaffarian and Dr. Ludwig write in JAMA. “Moreover, a global limit on total fat inevitably lowers intake of unsaturated fats, among which nuts, vegetable oils and fish are particularly helpful.”

DEFINING “HEALTHY”: The realization that all fats are not equally to be avoided has been slow to penetrate official standards as well as the popular mindset (see next page), however. It’s not just the Nutrition Facts panel that’s behind the times: The FDA’s definition of “healthy” as a claim allowed on packaging still includes a requirement that a product be low not just in saturated fat but also in total fat. (See our June Special Supplement for more on these often-confusing label terms.)

Earlier this year, that outdated definition led the agency to formally warn makers of a popular brand of snack bars to stop marketing several of their products as “healthy.” But the fats in those snack bars mostly come from healthy sources such as nuts and vegetable oil and are mostly unsaturated. The FDA’s definition of “healthy,” however, has no similar limits on sugar, refined grains or starch.

Other federal programs must adhere to the dietary guidelines, which still limit total fat. So the National School Lunch Program bans whole milk because of its fat content, but allows skim milk that’s been sweetened with sugar. The National Institutes of Health’s “We Can!” program to promote healthy eating recommends that families and children eat “almost anytime” fat-free salad dressing and ketchup (both sources of sugar). But the program advises eating “sometimes or less often” all vegetables with added fat, nuts, peanut butter, olive oil and tuna canned in oil. Whole milk and “eggs cooked with fat” are relegated to the same category as candy, chips and non-diet soda.

PREFER A HEALTHY PATTERN: “This is not to say that high-fat diets are always healthy, or low-fat diets always harmful,” the experts’ Times op-ed cautions. “But rather than focusing on total fat or other numbers on the back of the package, the emphasis should be on eating more minimally processed fruits, nuts, vegetables, beans, fish, yogurt, vegetable oils and whole grains in place of refined grains, white potatoes, added sugars and processed meats. How much we eat is also determined by what we eat: Cutting calories without improving food quality rarely produces long-term weight loss.”

You don’t need to wait for the release of the 2015 dietary guidelines, which may make changes as suggested by the DGAC. When eyeing the Nutrition Facts panel (see box) or other labeling, you can stop worrying about total fat. Look at the numbers for nutrients you probably need more of, such as dietary fiber, vitamins and minerals other than sodium. For choosing healthier breads, cereals and other carb-rich foods, Dr. Mozaffarian recommends foods with at least 1 gram of fiber for every 10 grams of total carbohydrates, rather than focusing on sugars or fiber alone. (For more on the importance of dietary patterns and food choices—not simply calories—see our August 2015 Special Report.)

But, as Dr. Mozaffarian and Dr. Ludwig emphasize, healthy eating is about more than numbers and labels. That DGAC report, notable for its omission of limits on total fat, is a good place to start in planning your meals and grocery shopping. According to the report, a “healthy dietary pattern is higher in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low- or nonfat dairy, seafood, legumes and nuts, moderate in alcohol (among adults), lower in red and processed meats, and low in sugar-sweetened foods and drinks and refined grains.”

Understanding the latest evidence about total fat intake and health can help you to rethink how you use nutrition labels. Here’s an updated way to look at the Nutrition Facts panel, even as the FDA considers possible revisions, using peanut butter (high in healthy fats) as an example:

– Compare the serving size to how much you actually eat. If a “serving” of peanut butter is two tablespoons but you normally spread three, take these numbers times 1.5. (The FDA plans to update serving sizes to make them more realistic.)

– Tufts’ Dr. Mozaffarian advises, “Only pay attention to total calories if comparing two similarly unhealthy foods: e.g., two bagels, two candies, two processed meats. When eating minimally processed healthful foods, don’t focus on calories, but eating until you’re satisfied.”

– Ignore the number of calories from fat, which the FDA has already proposed deleting from revised labeling.

– Don’t worry about the total fat number or percentage. You can, however, subtract the saturated fat number from the total fat to calculate the grams of unsaturated (mono- and poly-) fat. Exact amounts vary by brand, but a typical serving of peanut butter might contain about 9 grams of monounsaturated fat and 4.5 grams of polyunsaturated fat. Foods higher in unsaturated fats, as a proportion of total fat, are generally better options.

– Avoid any food listing more than zero grams of trans fats. While some foods labeled as zero might still have trace amounts (less than 0.5 grams) of industrial trans fats, by mid-2018 even these will be gone. (See the September newsletter.)

– Most people don’t need to worry about dietary cholesterol intake. If you have diabetes or you’re at higher risk for diabetes, check with your physician.

– Avoid products higher in sodium. Compare sodium levels in different products in similar categories (e.g., two breads, two soups, two cheeses) and always move toward lower sodium, with a goal of less than 2,000 milligrams a day.

– When choosing grains or other carbohydrate-rich foods, aim for at least 1 gram of fiber for every 10 grams of total carbohydrates (a 1:10 ratio).

“Most important, don’t pick or avoid any food based on a single number on the label,” says Dr. Mozaffarian. “Indeed, foods without labels are probably the best bet, most of the time, in the first place.”

Consumers and most of the media havent gotten the message about total fat. Just recently, a Sunday newspaper supplement listed five keys to preventing heart diseaseamong them, Avoid fats. A popular healthy-cooking magazine recommended using peanut butter powder in a recipe to avoid the (mostly unsaturated) fat in peanut butter. No wonder that a 2014 Gallup poll found a majority of Americans still trying to cut down on their intake of all fats. Dr. Mozaffarian and Dr. Ludwig comment, This fear of fat also drives industry formulations, with heavy marketing of fat-reduced products of dubious health value.