Popular coverage of diet and weight-loss strategies often summarizes the bottom line with a twist on President Bill Clinton’s campaign mantra, “It’s the economy, stupid.” When it comes to managing your weight, as this line of thinking goes, “It’s the calories, stupid.”

But a new study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition challenges this conventional wisdom. “It builds on earlier work that suggests all calories are not the same,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH, dean of Tufts’ Friedman School and senior author of the study. “All foods have complex mechanisms that help or hinder weight long-term. The simple math of calories in versus calories burned is true if you’re testing food in a test tube. But human beings are not just inert buckets to put calories in.”

Most intriguingly, he adds, the results show that over the long term, foods interact in a synergistic way.”Our findings suggest we should not only emphasize specific protein-rich foods like fish, nuts and yogurt to prevent weight gain, but also focus on avoiding refined grains, starches and sugars in order to maximize the benefits of these healthful protein-rich foods, create new benefits for other foods like eggs and cheese, and reduce the weight gain associated with meats.”

PROTEIN PICKS: People tend to gain weight as they age—the infamous “middle-age spread”—which increases their risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and even cancer. Excess weight is also a factor in the effects of arthritis. But adjusting your diet to keep off those pounds as you age can be a challenge, with sometimes confusing or contradictory advice.

Jessica Smith, PhD, a visiting scholar at the Friedman School and research fellow at Harvard who was first and corresponding author on the new study, says, “There is mounting scientific evidence that diets including fewer low-quality carbohydrates, such as white breads, potatoes and sweets, and higher in protein-rich foods may be more efficient for weight loss. We wanted to know how that might apply to preventing weight gain in the first place.”

Researchers examined up to 24 years of data on 120,784 men and women from three large, long-term studies—the Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study II and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. Participants, who were initially free of chronic disease or obesity, completed detailed food questionnaires. Their weight gain was measured at four-year intervals, and results were adjusted for lifestyle changes including physical activity, sleep duration and TV habits, as well as total calorie intake.

Participants tended not to substitute one protein food for another—fish for red meat, for example—but rather to switch from proteins to carbohydrates. That’s in keeping with the ill-fated emphasis on low-fat dieting, in which many Americans replaced fatty foods with refined carbohydrates—and gained weight.

The study found varying associations between protein foods and weight:

– Meats, chicken with skin and regular cheese were associated with weight gain.

– Milk, legumes, peanuts and eggs were not associated with weight gain or loss.

– Yogurt, peanut butter, walnuts and other nuts, skinless chicken, low-fat cheese and seafood were actually associated with relative weight loss.

“The fat content of dairy products did not seem to be important for weight gain,” Smith adds. “In fact, when people consumed more low-fat dairy products, they actually increased their consumption of carbs, which may promote weight gain. This suggests that people compensate, over years, for the lower calories in low-fat dairy by increasing their carb intake.”

As for red meat, Dr. Mozaffarian says, “Regardless of fat content or whether it was processed, consumption was linked to weight gain. This is interesting in light of the ‘Paleo diet’ fad, which promotes meat intake.” (See our July Special Report.)

CARB QUALITY: When researchers looked at carbohydrate choices, they found a relationship between glycemic load (GL) and weight changes. Based on the glycemic index, which measures how rapidly a food boosts blood sugar, glycemic load also factors in typical serving sizes. High-GL foods, such as white bread, white potatoes and white rice, are considered lower-quality carbohydrates and were associated with weight gain.

“There is still debate about the independent value of glycemic load in weight maintenance,” says Dr. Mozaffarian, “but it’s clear that there is an effect. It’s not all about glycemic load; fiber and whole grains are also important.”

Potatoes were the number-one culprit in weight gain among study participants. “It didn’t matter whether they were boiled or baked or mashed or French fries or had fat in them or didn’t have fat in them,” he adds. “It was the starch.”

The findings also spotlight the role of starches in promoting weight gain. In the new study, the weight gain associated with starches from refined grains was identical to that from sugar-sweetened foods. Since 2005, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans have focused on reducing added sugar, as in sweetened soft drinks. But starches from refined grains add up to double the intake of added sugars for most Americans. For the first time, the report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee also singles out starches along with sugars.

“Some breakfast cereals, for example, are almost entirely refined starches,” Dr. Mozaffarian says. “If you buy one with slightly less sugar but far more starch, that’s not a good trade-off.”

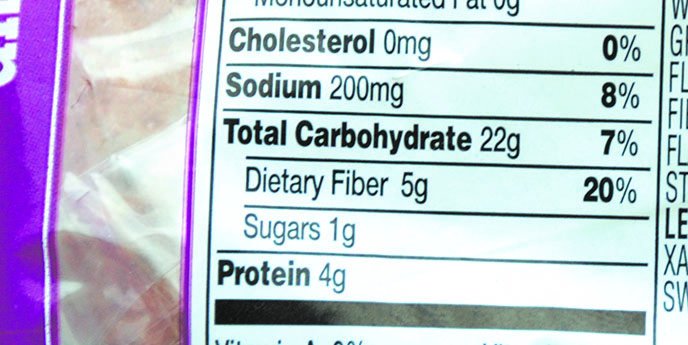

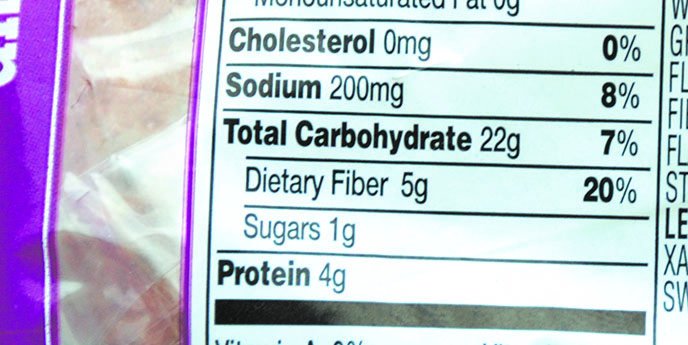

A simple rule of thumb, he says, is to look for foods whose ratio of total carbohydrates to fiber is 10:1 or less. So, for example, a product such as white bread with 15 grams of carbohydrates and one gram of fiber would have a ratio of 15:1—not a good choice.

SYNERGY, GOOD AND BAD: If you’re choosing weight-promoting foods such as red meat, the study found that compensating with low-GL foods could actually help mitigate weight gain. On the other hand, combining proteins linked to weight gain with high-GL foods exacerbated the effects.

As Dr. Mozaffarian puts it, “If you’re having salmon and potatoes and trying to decide about having cheese on top, better to have the salmon plus cheese and drop the potatoes, even adding a salad or fruit on the side.” Similarly, eating a burger with a salad instead of fries could moderate the meat’s impact on weight; even better, he suggests, would be to eat it without the starchy bun.

A similar synergistic effect was seen for foods like eggs that were neutral in their associations with weight gain or loss. When servings of these foods were increased in combination with increased GL, they were linked to weight gain. But when servings of eggs were increased in combination with decreased GL, participants actually lost weight.

Lower-GL choices also magnified the weight-loss associations of protein foods such as fish.

COMMON SENSE: Adapting our dietary choices and even our health policies (see box, previous page) to science that says it’s not just the calories that count may take some rethinking, Dr. Mozaffarian allows. “The food you eat affects your brain’s reward systems, your insulin levels, your liver function, your microbiome, your fat-cell function. We have really complex built-in mechanisms to regulate our weight.”

That complexity is why a three-ounce salmon fillet and a baked potato, eaten without the skin, might have roughly the same 145 calories, but their long-term effect on your weight appears to be quite different. Any diet can help you shed pounds in the short term by cutting calories, but over time it’s not just a matter of calories in versus calories burned.

“Saying that obesity is a problem of energy balance is like saying fever is caused by temperature imbalance,” says Dr. Mozaffarian. “It’s not about diet quantity; it’s about diet quality.

“It’s a radical message, but on the other hand it’s just common sense,” he adds. “The more we learn in nutrition science, the more we return to common sense.”

The Affordable Care Act will require chain restaurants to post calorie counts for all their menu items. But recent research suggests that not all calories are equal when it comes to their effects on weight. Until our calorie-focused policies catch up to the science, youll want to dig a little deeper. A menu item with 1,200 calories isnt necessarily a better choice than one with 1,400 calories, for example, if the lower-calorie option has more starch (such as in pasta, white bread or potatoes) and gets its protein from red meat. You might be better off with 200 more calories if they come from fish or skinless poultry, with more vegetables and less starch.

Heres another reason not to judge foods by their calorie counts alone: The numbers on the Nutrition Facts panel for some foods may be wrong. According to USDA research, the counts for some protein-rich foods and nuts overstate the calorie content by as much as 25%. (Sorry, but the calorie numbers on junk foods and other choices high in processed carbohydrates are relatively accurate.)

Calories are measured by burning a food in a device called a calorimeter to see how much it raises the temperature of water. One calorie is the amount required to raise the temperature of one gram of water by one degree Celsius. But the calories on food labels are actually kilocaloriesshorthand for 1,000 such calories. And rather than actually burning up foods, label calorie counts are calculated based on four (kilo)calories per gram of protein, nine per gram of fat, and four per gram of carbohydrate (after subtracting grams of fiber).

This system fails to take into account the digestibility of different foods; the body expends more energy breaking down meat and nuts. Moreover, foods such as nuts are not completely digested and so pass through the body with some calories intact. Almonds, for example, are listed as containing 160 calories in a one-ounce serving, but a 2012 study found the body actually obtains only 129 of those calories.