Already a concern for older adults who lack adequate stomach acid to extract natural vitamin B12 from food, B12 deficiency may be more widespread than previously thought. The largest study to date of the effects of popular heartburn and ulcer medications on the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency reports a potentially serious problem. The study found patients who took the most popular acid-suppressing drugs, called proton-pump inhibitors or PPIs, for more than two years were 65% more likely to be deficient in vitamin B12.

There is more low vitamin B12 status and deficiency in the population than is appreciated, because of the lack of use of sensitive tests, says Irwin H. Rosenberg, MD, editor of the Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter. So many people take proton-pump inhibitors now for indigestion or reflux. These work by shutting off the gastric acids, putting the user at risk of food B12 malabsorption.

Some 157 million prescriptions were written last year for PPIs, which are marketed under brand names such as Nexium, Prilosec and Prevacid. Medications called histamine 2 receptor agonists (H2RAs), sold as brands including Tagamet, Pepcid and Zantac, can also interfere with B12 absorption by slowing the release of stomach acids. The new study found H2RAs were also associated with B12 deficiency, but the additional risk was less pronounced (31%).

Douglas A. Corley, MD, and colleagues at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., compared the medical records of 25,956 adults diagnosed with vitamin B12 deficiency against those of 184,199 free of deficiency. In results published in JAMA, among patients who had used PPIs for at least two years, 12% were vitamin B12 deficient, compared with 7.2% in the control group. Surprisingly, the association was strongest among PPI patients younger than 30, a group not ordinarily viewed as at risk for B12 deficiency. Previous small studies of acid-suppressing drugs had focused on older individuals, who are also at risk because their natural ability to produce stomach acids declines with age.

WHEN SYNTHETIC IS BETTER:Although B12 is a water-soluble vitamin, when naturally present in foods such as meat, fish, poultry, eggs and dairy products, the vitamin is bound to proteins in the food. In your stomach, hydrochloric acid and gastric protease (an enzyme that breaks down proteins) release the B12 for your body to use. That doesnt work as well when age or medications reduce those acid levels.

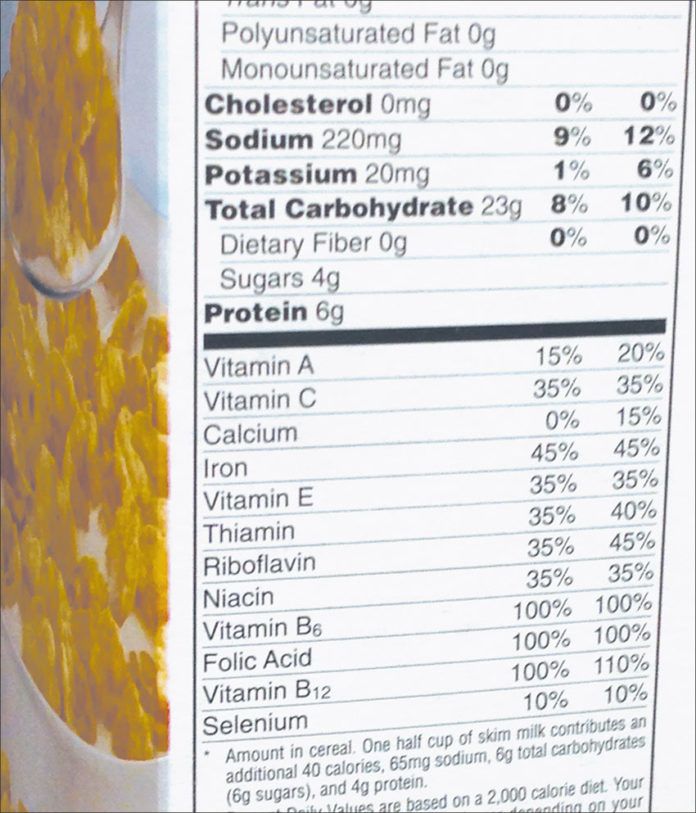

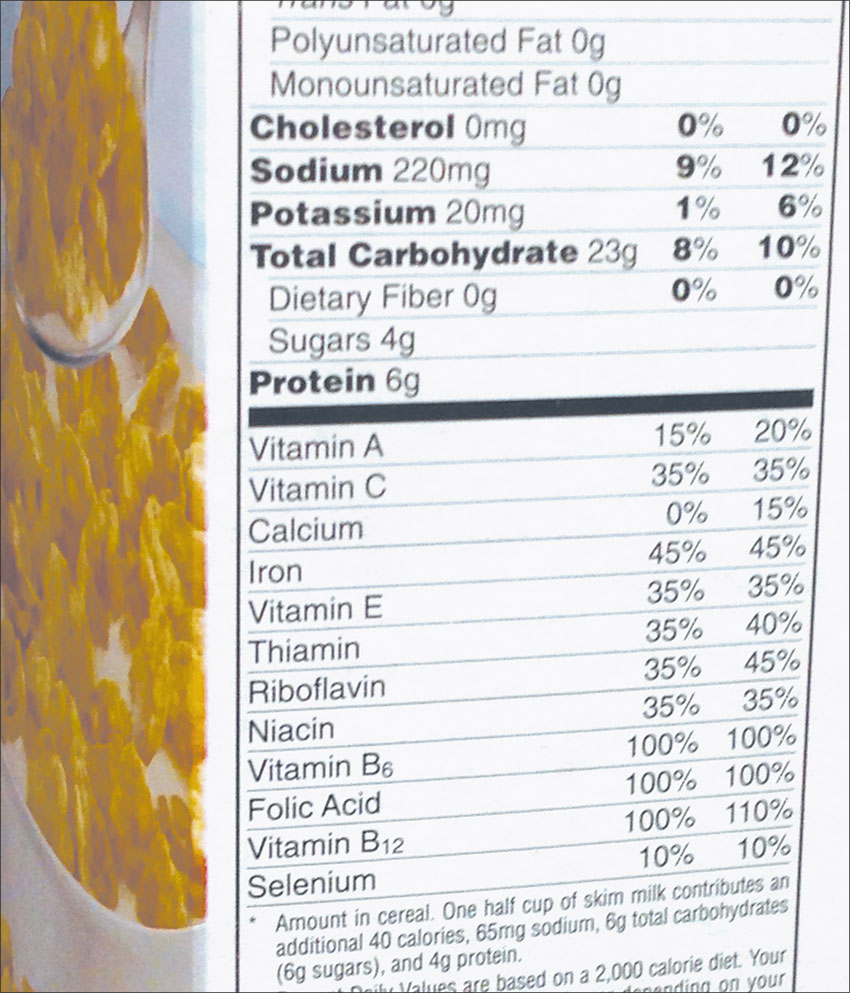

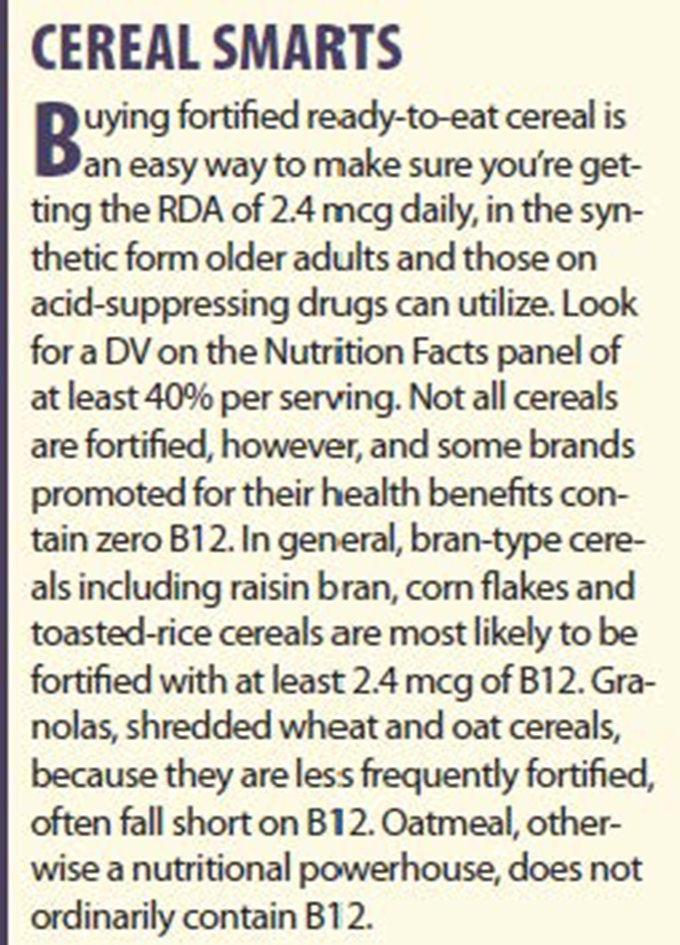

But the synthetic form of vitamin B12 used in supplements as well as in fortified foods such as breakfast cereals is already in a free form that doesnt require stomach acids to be utilized. Depending on the brand, one bowl of fortified cereal can provide all the B12 you need in a day-2.4 micrograms (mcg). Thats the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for most adults (pregnant and lactating women need more). Be aware, however, that the Daily Value (DV) for B12 that you see reflected in percentages on Nutrition Facts labels is much higher, 6.0 mcg.

Note that the FDA does not require food labels to list B12 content unless a food has been fortified with this vitamin.

Most supplements containing vitamin B12 deliver much more than the RDA or the DV, also in synthetic form thats ready to be put to work. Theres no harm in extra B12, but little evidence of any benefit.

DISCOVERING DEFICIENCY: In publishing their new study, Dr. Corley and colleagues did not recommend that patients taking acid-suppressing drugs stop taking them. But they did note, This raises the question of whether people taking these medications for long periods should be screened for vitamin B12 deficiency.

Only a blood test can determine whether a person is actually deficient in vitamin B12. Blood levels of below 150 picograms per milliliter (pg/mL) are clearly low. Levels between 150 and 300 are uncertain, says Tufts Dr. Rosenberg, who has served on expert panels about B vitamins for the World Health Organization, the Institute of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Borderline deficiency can be determined by other tests including blood methylmalonic acid or homocysteine.

Vitamin B12 is important for proper blood-cell formation, neurological function and DNA synthesis. Clinical deficiency, advanced beyond low B12 in blood tests, can manifest as anemia, fatigue, weakness, soreness of the mouth or tongue, constipation, loss of appetite and weight loss. Neurological changes, such as numbness and tingling in the hands and feet, can also occur, along with difficulty maintaining balance. Vitamin B12 deficiency has been associated with depression, confusion and poor memory. For more about vitamin B12, see our July 2011 Special Report.