If these thirsty, sweaty summer days have you worrying whether youre getting eight glasses of water a day-as conventional wisdom says you should-you need to take a closer look at the facts versus the fictions about hydration.

There is little scientific basis for stating a daily requirement for eight glasses of water, says Irwin H. Rosenberg, MD, University Professor at the Friedman School and editor of the Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter. Actual fluid needs vary widely among individuals, and depend upon body size and energy expenditure through exercise, among other factors.

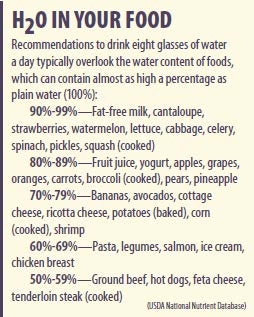

For most people, according to the Institute of Medicine, fluid intake, driven by thirst… allows maintenance of hydration status and total body water at normal levels. Moreover, despite what you may have heard, the water in caffeinated beverages such as coffee and tea does count toward keeping you hydrated. So does the fluid content of foods, which adds up to about 22% of the average Americans water intake.

While you dont need to worry about the eight glasses a day rule, as you age you might need to pay extra attention to your bodys hydration needs. Older people often have a reduced sensation of thirst, so its easier to miss the warning signs that youre dehydrating. Older individuals also tend to have lower reserves of fluid in the body and to drink insufficient water following fluid deprivation to replenish their body water deficit.

Because of their low water reserves, Dr. Rosenberg says, it may be prudent for the elderly to learn to drink regularly when not thirsty and to moderately increase their salt intake and eat foods high in potassium when they sweat.

BEHIND THE NUMBERS: The eight glasses a day myth probably originated with a 1945 finding that people need 64 ounces of fluids (the equivalent of eight eight-ounce glasses) daily. But even that recommendation factored in the fluids in food as well as coffee, tea and soda-not just water from the tap. In 2002, an analysis by Heinz Valtin, MD, of Dartmouth Medical School-a kidney specialist and author of two widely used textbooks on the kidneys and water balance-found no scientific proof for the eight glasses a day rule of water intake. Similarly, in 2008, a review of the evidence published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology concluded that no single study supports this rule.

As for what counts toward fluid intake, a 2000 University of Nebraska study found no significant differences whether the beverages people consumed were carbonated, diet or contained caffeine. Researchers saw no evidence that the diuretic effects of caffeinated beverages cancel out their hydration benefits, concluding: Advising people to disregard caffeinated beverages as part of the daily fluid intake is not substantiated by the results of this study.

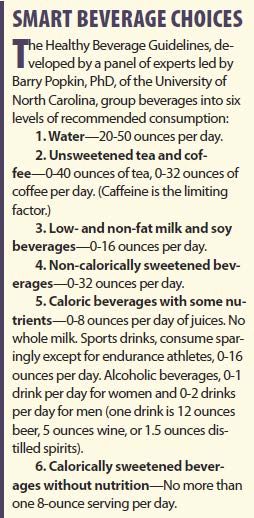

An Institute of Medicine expert panel in 2004 echoed that conclusion. Most Americans, the experts found, get plenty of water not only from plain water but also from food, milk, juice and even coffee, tea and alcoholic beverages. The share of that fluid intake coming from caloric beverages has sharply increased in recent years, however, contributing to the obesity epidemic. Total daily fluid intake by US adults increased from 79 fluid ounces in 1989 to 100 ounces in 2002-with the increase coming entirely from caloric beverages.

HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH?:Water makes up about 75% of body weight in infants and 55% of body weight in the elderly. Every cell in your body needs water to function. Water transports nutrients and oxygen throughout the body, and carries away waste materials. For a substance so essential to life, however, surprisingly little is known about how much water the human body actually needs.

Surveying the subject in Nutrition Reviews, Dr. Rosenberg and Tufts colleague Kristen E. DAnci, PhD, and Barry Popkin, PhD, of the University of North Carolina noted, There are major gaps in knowledge related to measurement of total fluid intake and hydration status at the population level, and few longer-term systematic interventions and no published randomized-controlled longer-term trials.… Beyond the circumstances of dehydration, we do not truly understand how hydration affects health and well-being, even the impact of water intakes on chronic diseases.

While research supports the importance of water intake in preventing and counteracting dehydration, they added, more is not necessarily better: Little research supports the notion that additional water in adequately hydrated individuals confers any benefit.

FLUIDS FOR HEALTH & COGNITION: An important aspect of healthy hydration relates to the absolute requirement to regulate the bodys temperature. Good hydration contributes to that important function in several ways, including sweating to lose excess heat. (Another reason older people need to be more aware of their bodys fluid needs is that the elderly are less able to compensate for the increased blood thickness that results from the loss of water through sweating.)

Dehydration can also affect your brain, at least in the short term, though research on these effects is inconsistent. In some studies, cognitive performance was not significantly affected in ranges from 2%-2.6% dehydration. In other studies, when participants were dehydrated to approximately 2.8%, performance was impaired on tasks involving visual perception, short-term memory and psychomotor ability. In a series of studies using exercise in conjunction with water restriction as a means of producing dehydration, Tufts DAnci and colleagues observed only mild decreases in cognitive performance in healthy young men and women athletes. Its possible that heat-stress rather than dehydration alone may affect cognitive performance. Mood and alertness seem to suffer the most when you dont get enough fluids.

Dehydration can also cause headaches, although the folk wisdom that drinking more water can stave off headaches has not been extensively studied. Water intake seems to be modestly associated with reductions in headache intensity and duration, but not the number of headache episodes.

The most obvious way in which hydration affects health is in the function of the kidneys, which play a key role in regulating the bodys fluid balance. The kidneys work more efficiently when the body has plenty of water. Deprived of adequate fluids, the kidneys must work harder and are more stressed.

MORE MYTHS: Another area popularly associated with the need to drink plenty of water is gastrointestinal function. But Dr. Rosenberg and colleagues wrote, Inadequate fluid consumption is touted as a common culprit in constipation, and increasing fluid intake is a frequently recommended treatment. Evidence suggests, however, that increasing fluids is only of usefulness in individuals in a hypohydrated state [lacking adequate water], and is of little utility in euhydrated individuals [having normal water content].

Youve probably also heard that drinking lots of water will improve your skin or complexion. Drinking those eight or more daily glasses of water is supposed to flush toxins from the skin or give you a glowing complexion.

In their review, Dr. Rosenberg and colleagues say there is a general lack of evidence to support these proposals. Its true that your skin contains about 30% water. And increased water intake, particularly if youre not getting enough, can improve skin hydration and thickness. Adequate skin hydration, however, is not sufficient to prevent wrinkles or other signs of aging, which are related to genetics, and sun and environmental damage. Applying topical emollients, such as skin creams, on the outside of your skin will improve the look and feel of dry skin more effectively than adding water from the inside.

The evidence that getting plenty of fluids can prevent chronic diseases is also limited. Not surprisingly, strong evidence links good hydration with reduced risk of kidney stones and other stones in the urinary system. According to Dr. Rosenberg and colleagues, the evidence is less strong for reduced incidence of constipation, exercise asthma and hyperglycemia in diabetes. Clinical trials are needed to confirm the benefits of good hydration against urinary tract infections, hypertension, heart disease and blood clots.

That means you should be skeptical about the claims of water cures in popular books. Drinking water beyond your bodys basic needs has not been shown to help to cure heart disease, diabetes, cancer or chronic pain.

EXERCISE AND FLUIDS: Answering the question of how much water (or other fluids) is enough also depends on how active you are. In an hour of exercise, your body can lose as much as a quart of water that must be replaced. Keep in mind that when older people exercise, they sweat less than younger athletes-presenting a challenge to the bodys internal thermostat.

Fitness can actually reduce your risk of dehydration. Fit people of any age also sweat more, keeping the body cool, and have more diluted sweat, losing fewer electrolytes as they perspire.

Your exercise and overall activity level may also be key to answering the question: How much water do you really need, including that obtained from consuming liquids as well as from fluids in foods? Much as your body size and activity level affect how many calories you need, a similar rule of thumb might apply to fluid intake.

Dr. Rosenberg and colleagues suggested that for every calorie you ought to consume, your fluid needs would be about one milliliter. So, for example, if your physical activity level justifies consuming 2,000 calories a day in food, you probably need two liters (2,000 milliliters) of fluid. Thats almost 68 fluid ounces, or about eight and a half cups. If that sounds suspiciously like the old eight glasses of water a day rule, keep in mind that this calculation includes all the beverages you consume as well as the fluids in your food. People who exercise more and can consume more daily calories would also need more daily fluids.

So, even on these hot summer days, dont be afraid of breaking a sweat. Just avoid the hottest part of the day and too much sun-and drink plenty of water.

A quick Internet search for distilled water turns up a stunning variety of opinions about its healthfulness, from Why you should drink distilled water to Early death comes from drinking distilled water.

The reality is probably somewhere in-between. No reputable study has reported magical properties for distilled water, which has been evaporated and then re-condensed to purify it. While some research has shown a benefit from the minerals in tap water-missing from distilled water-your bodys need for minerals is largely met through foods, not drinking water. If youre worried about contaminants in your drinking water, there are less expensive and less extreme solutions than buying distilled water.

You may have read about alkaline water (also called ionized water). Its proponents-many of whom sell gizmos to make alkaline water-claim that by giving water a higher pH (less acidic), alkaline water can boost metabolism, neutralize acid in your bones and bloodstream, help you absorb nutrients, prevent disease and even slow the aging process.

In evaluating such claims, keep in mind that water can only be alkaline to the degree that it contains minerals that can be ionized. Alkaline water, just like high-alkaline foods, is quickly counteracted by the strong acids in your stomach. (Foods effect on the bodys acid-alkaline balance depends on the residues they produce, rather than the acidity of the food itself.)

Claims for health benefits from alkaline or ionized water have never been tested in well-controlled clinical trials. And chemistry experts say the claims simply dont make scientific sense.