Each year, one in six Americans gets sick from eating contaminated food. In the spring of 2018, people across the United States and Canada began falling ill with common food poisoning symptoms: diarrhea, stomach pains, nausea, and vomiting. In the following months, nearly 200 people became ill, and five people died. CDC investigators traced the infection to Romaine lettuce grown in one particular region of the US. Any type of food, even healthy greens, can harbor pathogens. Fortunately, following some simple food safety tips, and paying attention to warnings and recalls, can prevent the majority of foodborne illnesses.

Foodborne Illness Basics: Researchers have identified more than 250 foodborne diseases, most of which are caused by a variety of bacteria, viruses, and parasites. “There are some illnesses, like botulism, that are due to toxins secreted by bacteria that have grown in the food,” says John Leong, MD, PhD, professor of molecular biology and microbiology. “But most often, foodborne illness is caused by ingesting microbes that then grow in the intestine and cause disease.” It is common to blame symptoms on the last thing eaten, but symptoms can begin anywhere from one hour to several weeks after ingestion, depending on the germ or toxin causing theproblem.

While symptoms nearly always resolve on their own, foodborne illnesses can sometimes be life-threatening. Anyone with severe symptoms, such as diarrhea that lasts more than three days, high fever, blood in stools, or frequent vomiting that makes it impossible to keep liquids down, should seek medical attention. Groups at particular risk for infection and complications include older adults, pregnant women, young children, and people with weakened immune systems (such as people with diabetes, liver disease, kidney disease, organ transplants, HIV/AIDS, or those receiving chemotherapy or radiation treatment). Leong points out that stomach acid kills many pathogens, so people who have decreased stomach acidity (for instance older adults, those on acid-blocking medications, or post-gastric bypass patients) are at increased risk for foodborne illness.

Food Safety: Following basic food safety rules can help prevent foodborne illness when cooking at home, picking up takeout, eating out, or at summer cookouts. Many people have survived eating pizza from the box that sat out all night, but, the fact is, allowing food to remain at room temperature (or anywhere in the “danger zone” between 40 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit) gives germs a chance to grow, so the CDC recommends getting those leftovers into the fridge within two hours or less. It is important to note that, if the bacteria release a toxin, reheating the food won’t get rid of the problem.

When deciding if prepared and packaged foods are safe, “sell by” dates are of little help. As long as they are stored properly, foods past their “Sell by…,” “Best if used by…,” and “Guaranteed fresh until…” dates are still safe. However, the USDA does advise following the “Use by…” dates. (See June 2016)

Fruits and Vegetables: Produce is responsible for nearly half of foodborne illness in the US, but that doesn’t mean health-promoting fruits and vegetables should be avoided. The benefits from a diet rich in plant foods definitely outweigh the risks.

Pathogens can take up residence on the surface of fruits and vegetables in the field, after harvesting, in storage, or in preparation. The best way get rid of these unwanted guests is plain water. The CDC recommends rinsing all fruits and vegetables under running water. Some of their other washing tips include:

-Start and finish with clean hands, utensils, and workspaces to avoid spreading germs.

-Don’t re-wash pre-washed, bagged greens. The risk of transferring bacteria already lurking in the kitchen is greater than the risk that some contaminants may have made it through the commercial washing process.

-Scrub sturdy produce, like melons or apples, with a clean brush.

-Don’t use soap. Washing with soap increases the risk of ingesting soap residue. The CDC also does not recommend special produce washes.

-Wash the peel or rind before peeling or cutting produce like oranges, cucumbers, or melons to avoid transferring surface pathogens to the clean interior of fruits and vegetables.

-Rinse even organic produce before eating. Organic foods are grown with fewer pesticides, but do not necessarily have fewer pathogens.

-Dry produce with a clean cloth or paper towel after washing.

-Germs like the moist interior of fruits and veggies, so choose undamaged produce, and cut away any damaged or bruised areas before using. Once they’re cut, peeled, or cooked, get produce into a refrigerator within two hours, and keep them away from any raw animal products that might be in there to avoid cross-contamination.

-Proteins: Although fresh produce accounts for a greater percentage of illness, raw foods from animals (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and milk) are actually the most likely to be contaminated, so making sure these foods are properly handled and thoroughly cooked is essential to avoiding foodborne illness.

-Storage: Juices that may leak from packages can contaminate other food in the shopping cart, bag, or refrigerator, so always keep raw meat, poultry, and seafood separate from other foods.

-Prep: Keep meats, poultry, and seafood in the refrigerator when thawing and marinating, and don’t rinse them before cooking. Washing these foods has not been found to prevent illness, and it can spread bacteria to other foods, utensils, and surfaces, so the CDC strongly recommends against this practice.

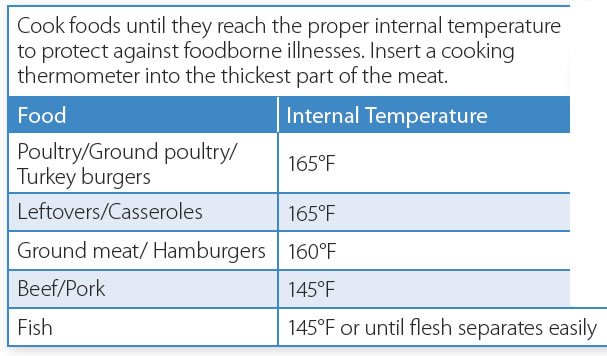

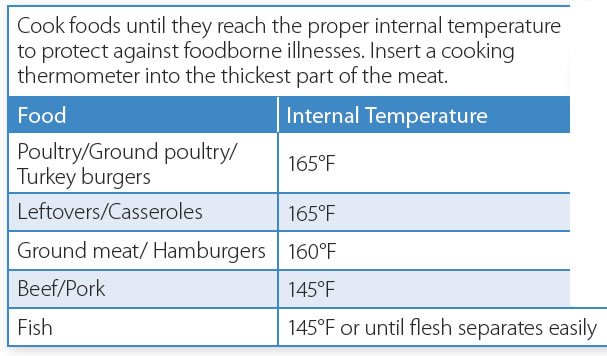

-Cooking: “Thorough cooking is important because high temperature kills microbes,” says Leong. A cooking thermometer is the only way to be sure food has reached the internal temperature necessary to kill all pathogens.

-Leftovers: Refrigerate any leftovers as soon as possible, but at most within two hours of preparation. Bacteria can begin to grow in any part of the meat that stays below 140 but above 40 degrees Fahrenheit, so cut up cooked turkeys and large roasts before refrigerating so they’ll cool faster.

-Eating out: Leong cautions that choosing to eat raw or undercooked animal products (like steak tartare, rare burgers, and sushi) comes with an inherent risk of food poisoning. If it is not possible to get leftovers to a refrigerator within two hours of eating, leave them at the restaurant.

Microbes thrive in moist, protein-rich environments, so raw eggs and unpasteurized dairy are prime breeding grounds. It’s recommended that eggs be cooked until the yolks are solid. Be aware that, while store-bought products in jars should be made with pasteurized eggs, raw or undercooked eggs can hide in fresh-made mayonnaise, Caesar dressing, custards, and some sauces. The CDC strongly recommends against drinking unpasteurized “raw” milk and eating cheeses and other products made from it. The risk of contracting a foodborne illness from raw milk is at least 150 times higher than the risk from pasteurizedmilk.

Summer Fun: It’s cookout and picnic season, and food poisoning danger rises with the summer heat. “Heat makes dangerous bacteria grow faster,” says Helen Rasmussen, PhD, RD, a senior research dietitian at the USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University. “If the temperature at your cookout is over 90 degrees Fahrenheit, don’t let food sit out for more than one hour.” Keep food on ice in a closed cooler, especially while waiting to grill raw foods, and put buffet bowls in pans of ice (refreshed regularly) to keep foods cold while serving.

When firing up the grill, laying out the picnic blanket, enjoying restaurant fare, or preparing a home-cooked meal, keep food safety in mind to help reduce the risk of ill effects down the line.

Take Charge!

The CDC recommends four simple steps to reduce food poisoning risk at home:

CLEAN: Wash hands and surfaces often. Wash hands thoroughly before and after preparing food and eating. If you want to clean potentially contaminated surfaces with bleach, use one teaspoon bleach to one quart water. More bleach is not better.

SEPARATE: Don’t cross-contaminate. Keep uncooked meat and poultry separate in the grocery cart, in the fridge, and on the counter and cutting board.

COOK to the right temperature. Use a meat thermometer. Don’t go by sight.

CHILL: Refrigerate promptly. The faster food gets cooled below 40 degrees Fahrenheit the better. Never leave perishable food in the “Danger Zone” between 40 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit for more than 2 hours.