If youre over 65 or approaching that age and still watching your weight, new findings suggest you may be worrying about the wrong thing. Its true that the obesity epidemic has exacted a serious toll on Americas health. But for older adults, maintaining muscle mass to ward off frailty-a condition called sarcopenia-is more important both to the length and quality of life than counting pounds. The popular Body Mass Index (BMI-see box), a calculation that combines weight and height, turns out not to be a very good predictor of health for older adults-for whom the rules about overweight may simply be different than for younger people.

Unfortunately, too many older people remain preoccupied with the numbers on their bathroom scale, comments Irwin H. Rosenberg, MD, editor of the Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter, who coined the term sarcopenia along with Tufts colleagues. This is a serious mistake. Losing weight is the wrong goal. You should forget about your weight and instead concentrate on shedding fat and gaining muscle.

In fact, Dr. Rosenberg points out, because muscle tissue weighs more than body fat, if you succeed in replacing fat with muscle, you wont lose much if any weight. But you would be much healthier as a consequence because youve altered your body composition in a favorable way. Youve decreased your risk for sarcopenia.

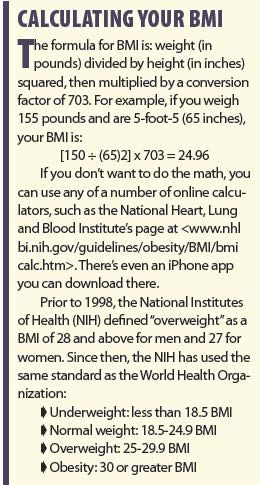

BMI SURPRISE: A new study, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, casts further doubt on the usefulness of BMI as a measure of health status for older adults. Australian researchers combined 32 prior studies totaling nearly 200,000 people age 65 or older, who were followed for an average of 12 years. They compared mortality risk with BMI to see if being overweight or obese increased participants odds of dying during the study periods.

Surprisingly, they found just the opposite. Those at greatest mortality risk were the thinnest seniors, with risk increasing at a BMI of 23 (towards the upper end of whats defined as a healthy body weight) and below. Risk actually rose with thinner BMIs; those with a BMI of 20.0 to 20.9 were 19% more likely to die than those between 23.0 and 23.9.

Conversely, those at lower mortality risk had BMIs of 24.0 to 30.9-a range including the high end of healthy, all those considered overweight, and the beginning of obesity. The very lowest risk fell between 27.0 and 27.9, the middle of the overweight category.

In an editorial accompanying the findings, John D. Sorkin, MD, PhD, of the Baltimore VA Medical Center, commented that, given the results, it behooves us to reconsider current weight-for-height guidelines.… We must be open to the possibility that the hypothesis that best weight-for-height in older adults is the same as that seen in younger adults may be wrong.

Older adults are susceptible to undernutrition due to physiological changes, chronic disease and other issues, the Australian scientists noted, meaning the healthiest seniors arent necessarily the thinnest. Focusing on weight rather than muscle mass also misses the risk factors for sarcopenia. And a little extra weight may actually be beneficial when an older person must recover from surgery or suffers from a condition like cancer.

Another recent study, also published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, adds evidence to the connection between weight and cancer survival: Among 175 cancer patients assessed before chemotherapy, average survival time for overweight and obese patients was significantly better than for normal and underweight patients. Those with sarcopenia, moreover, had the poorest prognosis, regardless of BMI.

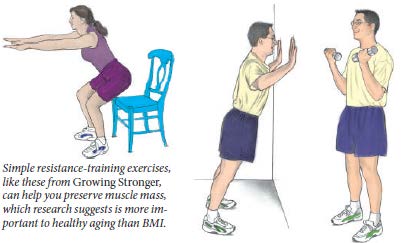

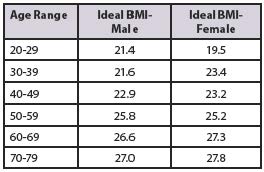

CHANGING IDEAL:Though surprising to most people, this isnt the first time science has challenged the assumption that older people should follow the same BMI guidelines as younger adults. In 1985, Reubin Andres, MD, long-time clinical director of the National Institute on Aging, used data from life-insurance companies to compare longevity and BMI. His findings showed that the ideal BMI-that associated with the lowest risk of chronic disease or mortality-increased with age:

In his editorial, Dr. Sorkin noted that those findings were controversial at the time, because they questioned the beautiful hypotheses that increasing weight is associated with increasing mortality and weight should remain unchanged throughout life.

In fact, BMI was never meant to be an assessment applied to individuals, rather than populations. Developed in the 1830s from measurements in men by a Belgian statistician studying how humans grow, BMI was adopted in the 20th century by insurance companies and obesity researchers.

One notable issue with BMI was spotlighted a few years ago by a study showing how NFL players are mostly overweight or obese according to BMI: It counts muscle the same as fat. Thats why NFL players-or Arnold Schwarzenegger, when he was Mr. Universe-could be considered obese, even when in superb physical shape.

APPLES VS. PEARS: In terms of health, more important than how many pounds youre carrying is where those pounds are distributed. Says Tufts Dr. Rosenberg, People who store much of their body fat above their hips have a higher risk for developing heart disease, stroke and diabetes than people who store fat below their hips. These body types are often called apple-shaped and pear-shaped, respectively.

The excess abdominal fat in apple-shaped individuals is metabolically active, linked to risk of insulin resistance, unhealthy cholesterol levels, high blood pressure and even Alzheimers disease. Though perhaps unattractive, fat carried around the thighs, buttocks and hips is comparatively inert and less likely to contribute to chronic disease.

The importance of where fat is stored leads to a test thats as simple as BMI but may be more reflective of health risks-the waist-hip ratio. Use a tape measure to determine the distance around your waist and around your hips. Divide the waist number by the hip measurement. (A 36-inch waist and a 44-inch hip circumference, for example, would work out to 0.82.) You need to worry about excess abdominal fat if the result is above 0.85 for women or 0.9 for men.

MUSCLES MATTER: Most important to health in the elderly, as seen in the cancer-survival study, is maintaining muscle mass, regardless of BMI, to avoid sarcopenia. Another new study, published in the American Journal of Medicine earlier this year, showed the relationship between body composition and longevity: UCLA researchers focused on 3,659 men age 55 and older and women age 65 and older whose body composition had been tested by bioelectrical impedance. That test uses a light electrical current to determine muscle versus fat; the water content of muscle tissue lets electricity pass more easily than does fat tissue.

Participants were tested between 1988 and 1994. Researchers then looked at a follow-up survey in 2004 to determine how many had subsequently died of natural causes. Those in the one-quarter of participants with the most muscle relative to height were significantly less likely to have died than those with the least muscle mass.

Rather than worrying about weight or BMI, commented Arun Karlamangla, MD, a co-author of the study, we should be trying to maximize and maintain muscle mass.

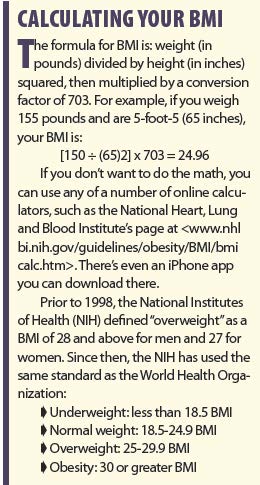

STAYING STRONG: How do you boost your muscle mass? In addition to aerobic exercises, such as brisk walking, which can burn fat and improve cardiorespiratory fitness, you need to incorporate resistance training into your fitness regimen. This can be as simple as squatting in and out of a chair or stepping up and down on a stair, or basic exercises using inexpensive hand weights. (See illustration.) Ankle weights can help you further increase your strength as you get accustomed to the effort required.

The resistance-training regimen in Growing Stronger, a book developed by Tufts experts in coordination with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are a good start. You can download the entire 126-page book for free at

Guidelines from the American College of Sports Medicine suggest strength training two or three times a week. Be sure to give your muscles at least one day of rest between workouts. If you have the time to do resistance training three times per week (on non-consecutive days of the week, i.e. Monday, Wednesday and Friday), you will strengthen muscles a bit more quickly. If you can do it only one day per week when your schedule gets hectic, that is still better than nothing.

Whatever regimen you follow, make sure your muscles are really working. If you do two sets of 10 repetitions, you should feel your muscles working hard to complete those sets. That doesnt mean straining or injuring yourself; after your workout, you should be able to use your muscles without difficulty or pain.

Be aware, however, that your BMI might actually go up as you build your muscle mass. Thats OK-youll be healthier and less at risk for chronic disease, even if that number says otherwise.