Does the glycemic index of the foods you eat matter? That’s the question raised by a headline-making new study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, the OmniCarb study, which calls into question the notion of “good carbs” versus “bad carbs.” Some previous research—along with popular diet plans—suggested that it’s healthier to choose carbohydrate sources that raise blood sugar levels slowly. These “low-glycemic index” foods include most whole grains and non-starchy vegetables, as opposed to high-glycemic options such as white bread, potatoes and sugary foods.

Image © Thinkstock

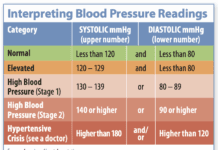

But the new clinical trial involving 163 people found no benefit from a low-glycemic diet on cholesterol levels, blood pressure or insulin sensitivity (a measure of the body’s response to insulin). Participants were mostly overweight and had high blood pressure, but did not have type 2 diabetes.

Researchers said the findings indicated that people free of diabetes who eat a generally healthy diet may not need to be guided by the glycemic index.

That caveat about a healthy diet is a big one, cautions Susan B. Roberts, PhD, Tufts professor of nutrition and founder of the online iDiet weight loss program <www.myidiet.com>. “I think the bigger issue here is what changes you can get people to make,” Roberts says. “It is all very well doing these controlled studies in clinical research centers, but the critical issue is changing what people want to eat, because that is the only thing that is going to stick.

Effectiveness trials testing programs that people implement themselves are the only way you can do that, and these tightly controlled efficacy studies really don’t add much to real-world help.”

BEHIND THE NUMBERS: Interest in the glycemic index has been rising since its development in 1981 by David Jenkins, MD, PhD, ScD, a professor of nutrition at the University of Toronto. Dr. Jenkins and colleagues tested 62 common foods on a group of healthy fasting volunteers, measuring the changes in blood-sugar levels over two hours. Foods were rated on a 100-point scale, with those such as starchy vegetables, breakfast cereals and baked goods boosting short-term blood sugar the most. The “glycemic index” (GI) concept was subsequently refined with the addition of “glycemic load” (GL), which took into account typical servings of each food.

By 2013, the spotlight on the glycemic index was such that a group of experts called for the numbers to be included on nutrition labels and emphasized in dietary guidelines. In a consensus statement (see the September 2013 newsletter), the experts concluded there was convincing evidence that low-GI/GL diets:

– Improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes.

– Reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.

– Reduce the risk of coronary heart disease, by improving cholesterol levels and markers of inflammation.

Research at Tufts has linked a low-GI diet with reduced risk factors for metabolic syndrome—a cluster of symptoms tied to diabetes and heart disease—and with lesser risk of advanced macular degeneration.

But much of the focus on the glycemic index has revolved around weight loss, which the OmniCarb trial didn’t address. Research by Tufts’ Roberts and several other research groups worldwide has found that watching your glycemic index does promote weight loss and prevents weight regain for about half the population. She notes, “Low-GI foods have also been shown to suppress hunger extremely well because the more stable blood glucose produced by these foods tells our food brain that all is well and we don’t need to eat again yet.”

ROTATING DIETS: Led by Frank M. Sacks, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, the OmniCarb study rotated participants through two of four different diets for five weeks at a time. All food was provided, and the diets were generally healthy with similar calorie totals. Two diets were slightly higher in carbohydrates than the typical US diet, with the other two somewhat lower. The lower carbohydrate intake was associated with improvements in cardiovascular risk factors including cholesterol, triglyceride and blood-pressure levels.

But few similar gains were specifically linked to a low-GI diet, in which participants were fed foods such as whole-grain bread and cereal, steel-cut oats, apples and non-starchy vegetables. Triglycerides were lower in the low-GI/low-carb diet compared to a high-GI/high-carb regimen, but there was no significant improvement in insulin sensitivity, blood pressure or cholesterol.

Critics of the new study, however, pointed out that the differences between the high- and low-GI diets were quite small. The brief, two-week “wash-out” period between each regimen may also have been too brief—a problem obscured by the statistical complexity of the study’s design. Dr. Jenkins suggested that because the study did not include people with type 2 diabetes, it may have failed to detect some of the cardiovascular benefits of low-GI diets.

Publishing their findings in JAMA, the researchers conceded that their trial did not attempt to “address the effect of glycemic index in a typical US diet.” But Dr. Sacks said, “The takeaway is a good message for people. They can pick foods that are part of a healthy dietary pattern without wondering if they’re high or low glycemic. They don’t have to learn that system.” People should choose whole grains, fruits and vegetables and high-fiber foods, he added, but because of the nutrients they contain, not their glycemic index.