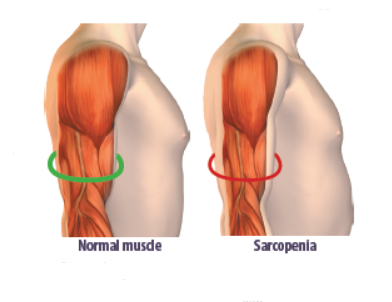

Sarcopenia, the gradual loss of muscle mass that can occur with aging, affects 15 percent of people over age 65, and 50 percent of people over age 80. As we lose muscle mass, we lose strength, and if we lose too much, our ability to function suffers. Fortunately, emerging research is shedding new light on the role dietary protein plays in maintaining muscle, functionality, and health as we age.

Some of this gradual, age-associated loss of muscle mass, strength, and function has to do with a decrease in activity, but not all of it. “Like many complex syndromes of older adults, many factors contribute to sarcopenia,” says Roger A. Fielding, PhD, director of the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) Nutrition, Exercise Physiology and Sarcopenia laboratory. “Decreased physical activity, hormonal changes, increase in low-grade inflammatory processes, and changes in dietary intake that include decline in protein intake are all involved.”

Photography Illustration by Marty Bee

Protein and Muscle: The body’s ability to manufacture muscle from protein decreases a bit with aging, so increasing dietary protein—in concert with muscle-building exercise—could help to maintain muscle mass and strength. “We know that in extreme conditions of protein malnutrition people lose muscle mass pretty rapidly,” says Fielding. “But even in older individuals who are taking in protein around the recommended levels, consuming lower amounts of protein is associated with higher rate of muscle loss than consuming higher amounts of protein.”

Paul F. Jacques, DSc, a professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and senior scientist at the HNRCA Nutritional Epidemiology Team, and his colleagues found higher protein intake may translate to less frailty, disability, or physical dysfunction “We found that higher protein intake was associated with a 30 percent lower risk of losing functional integrity with time,” says Jacques. “This is observational data, but it clearly demonstrates the potential importance of a higher protein diet.”

Being active is important as well. “Muscles tend to atrophy if we don’t use them,” says Fielding. “Our research suggests that more exercise and more protein may work synergistically to build and preserve muscle mass. In one study my colleagues and I found that participants who exercised and drank 20 grams of high-quality whey protein supplement daily had a significant increase in thigh muscle over time compared to those who exercised but drank a protein-free placebo. We used a protein drink for study purposes, but there are other components in food that have health benefits, so it’s always good to think about increasing protein intake with food first.”

Inflammaging: Meeting protein needs in aging populations appears to be important not only for maintenance of lean muscle mass, strength, and physical function, but also for potentially counteracting age-related changes in the inflammatory response. “Older age is associated with a state of low-grade, chronic inflammation we call ‘inflammaging,’” says Jacques. “Inflammaging is in turn associated with frailty, as well as cardiovascular disease and other chronic disease states and mortality.”

The relationship between inflammation and protein is complex. “Inflammation may lead to an increased need for dietary protein,” says Jacques. “But proteins can also be pro-inflammatory. We recently conducted a study to try to determine whether higher protein intake was helpful or harmful with regard to chronic inflammation and the maintenance of functional integrity with age. While most study participants were consuming adequate amounts of protein, lower protein intake was associated with higher inflammation scores. The group of people who consumed the least amount of protein had inflammation scores twice as high as the group who consumed the most protein. This suggests that, while there is no evidence that it combats inflammation, higher protein intake may help reduce the burden of frailty, sickness, and disease that is associated with the chronic inflammation of aging.”

Protein Pitfalls: While a little extra protein may be helpful, a lot is not. Too much dietary protein can put stress on the kidneys as they work to get rid of the excess, and while adequate dietary intake of protein is important for growth and maintenance of bone throughout life, too much protein can weaken bones. “Protein introduces an acid load that can be damaging to bone health,” says Bess Dawson-Hughes, MD, director of the Bone Metabolism Laboratory at the HNRCA. To counteract the acid, the body releases calcium ions from bones, potentially weakening them. “This increased acid load can be neutralized by consuming more fruits and vegetables,” says Dawson-Hughes. Even acidic fruits like citrus and tomatoes reduce acid load once digested and metabolized.

Although most U.S. adults get plenty of protein, older adults who get too little could be at increased risk for frailty and illness. Follow these tips to make sure you’re getting enough…but not too much:

- Include a protein-rich food in every meal. Try to spread protein intake out evenly throughout the day.

- Add more plant proteins (beans, lentils, soy, nuts), along with seafood and dairy, not just more meats and poultry.

- Choose proteins low in saturated fat and rich in nutrients, like plant foods and fish/seafood/poultry.

- Don’t overdo it. Too much protein can weaken bones and put stress on the kidneys.

- Balance increased protein with increased fruits and vegetables to protect bones. Eat these foods in place of refined carbs, sweets, and starches.

How Much, What Kind, and When: How much dietary protein a given person needs to support all of these roles depends on many factors, including level of physical activity, height/weight, health, gender, and age. Some studies suggest older adults may be able to stave off loss of muscle and function by consuming somewhat more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight (0.36 grams per pound). This works out to about 58 grams for someone weighing 160 pounds and 68 grams for someone weighing 190 pounds. While most adults in the U.S. have overall protein intake well above the RDA (consuming about 100 grams of protein a day when all sources are taken into consideration), some older adults (for example those with low appetite or dental problems or those following diets that restrict the categories of foods they consume) may not be eating enough in general. “Some people don’t get enough protein because their total calorie intake is low,” says Fielding. “The people in our studies were not eating very high amounts of protein,” says Jacques. “What we saw was that, within the range of usual dietary intake of American adults—the higher end is better.” (For context, even the group with the highest protein intake in Jacques’ study consumed less than the U.S. average of 100 grams of protein a day.)

Image © SEE D JAN | Getty Images

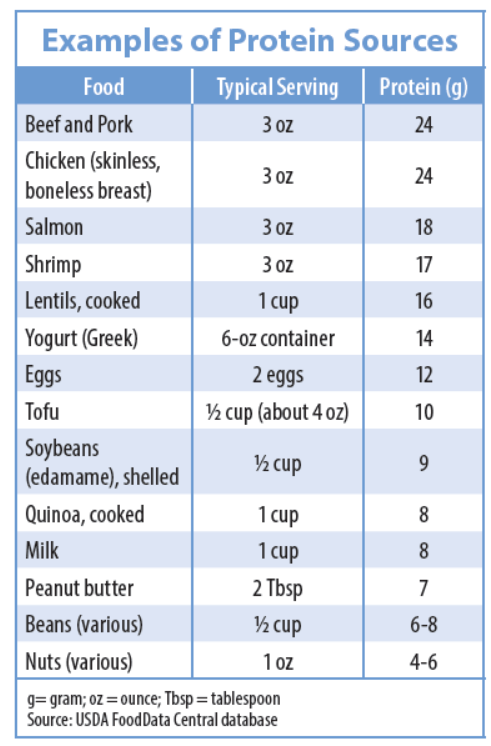

It’s important to keep in mind that “protein” does not just refer to meat. Dietary protein comes from both animal sources (meats, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy) and plant sources (like beans, lentils, and nuts.) The best way to get protein is to choose sources low in saturated fat and rich in nutrients and use them to replace starches and refined carbohydrate foods. Eggs and dairy products like milk and yogurt are excellent protein sources, as are all fish/seafood and poultry. Plant foods (particularly beans and legumes, but also nuts) contain protein that adds to your daily total, and plant proteins are a good choice. “While our study found total protein intake was associated with lower inflammation scores, the most favorable results were for participants who consumed higher levels of plant protein,” says Jacques, “but one can’t separate out protein from the matrix it comes in.” In other words, plant proteins come along with potentially anti-inflammatory and antioxidant components, while animal proteins naturally contain pro-inflammatory actors like heme iron. People who report consuming more plant protein tend to eat less animal protein, making it difficult for researchers to determine exactly which factors contribute the most benefit, but including more plant protein in place of animal protein could result in a less inflammatory dietary pattern overall (and support a healthier planet as well).

Timing of protein is emerging as an important consideration. Emerging evidence suggests spreading protein intake out throughout the day may be as important as getting enough. “It’s important to think about including protein-containing foods as a part of every meal,” says Fielding. “Most U.S. adults have a low-protein breakfast, a little protein at lunch, and consume most of their protein at the evening meal.”

To preserve muscle and bone, minimize inflammation, and maintain physical function, get enough healthy protein choices…but not too much. “Nutrition plays a big role in sarcopenia and other aspects of aging,” says Fielding, “one that we are continually working to understand.”

Why don’t you include white fish in your chart? Is it too low in protein to include?

White fish is not low in protein. It’s about 7 grams per ounce. I think researchers just listed some populate sources of protein

Good info here as I’m needing to lose weight-I’m almost 73. Want to cut way back on refined carbs and increase healthy protein in my diet as well as regular exercise.

Hi,

Women generally weigh less than men. Can you please offer estimates of grams per kilo (pounds) for women say 120 lbs to 140 lbs range as offered above for those weighing 160 lbs and 180 lbs??

Thanks,

Tanja

0.36 grams protein/pound of body weight x 120 pounds = 43 grams protein

0.36 grams protein/pound of body weight x 140 pounds = 50 grams protein

So, not too much and not too little, just right. But, wonder if we could have some hints of what is just right? Or a link, which takes in to account some variables, to help us find the approximate just right, please?

Agreed that the linked page considers appropriate factors presented clearly, but I wonder about their recommendations. While the Tufts article suggests older adults consume “somewhat more than the RDA of (0.8 g protein / kg body weight)”, this website suggests a very wide range, e.g., up to 1.2 g / kg (150% of RDA) for older adults and up to 2 g / kg (250% of RDA) for very active people. I have some concerns about getting too much protein, so would have liked more specificity from Tufts article about their thoughts on how much “somewhat more” than RDA is for older / active people.

Overall, this is an excellent article regarding the necessity of good and adequate protein. We have to understand that protein/amino acids is the only substance that helps us to not only decrease our risk of progressive and rapid sarcopenia, but to heal all of our tissues. The .36g/lb is for the “normal” adult. If you work out, you will get more tissue breakdown, so not a bad number is to bump up to about .45-.50g/lb.

At age 76, since I do intense powerwalking 3 to 4 times a week (average 5 miles, 16 min miles) and weight lifting twice a week, I try to get a minimum of .60g/lb(175 lb, so approx 100-110g). Make sure you adequately hydrate (60ish oz all fluids or very slightly yellow urine);That way there will not be issues with your kidneys

Thank you for this information 💁♀️

Important reminders for 90 yr olds. Very helpful to us.

For some reason, nutritionists appear to think that we weigh our food all of the time–and even do it only in grams, etc. Why isn’t the information provided in “lay” language, i.e., examples (chicken thigh) or at least pounds and ounces?

I’m 78 and on the Kidney Stone Diet. The Majority of foods listed above are not allowed according to the Harvard Health Study’s list of foods with high oxalates. It’s also been suggested that I decrease animal protein. In 1994 I was diagnosed, at Tufts Medical, with Hashimoto’s. Talk about being caught between a rock and a hard place.

Salmon and asparagus are my go to meals. No grains, no nuts, no soy, no spinach, no avocadoes, no potatoes, and more.

You have to treat the entire patient – not just the stone.