Dreamstime.com

Why are more than two-thirds of adults and about one-third of kids in the US overweight or obese? Two key factors in weight control are our eating habits and physical activity levels. But, complex interactions between our genetics and environmental factors may play a role, too. Scientists have been looking more closely at whether chemicals – such as in the food supply, household products, cigarette smoke and from industrial pollution – may play a role in weight gain and obesity.

“Some chemicals have been identified as endocrine-disrupting chemicals or obesogens,” says Beverly S. Rubin, PhD, an associate professor in the department of integrative physiology and pathobiology at Tufts University School of Medicine. “These may alter metabolic rate [how fast energy is burned] and increase the number and size of fat cells. In other words, they shift energy balance to favor storing fat.” But, it’s uncertain whether endocrine-disrupting chemicals actually increase our obesity risk. Here’s a closer look at the emerging science on obesogens.

Preliminary Research:

The best evidence for the existence of chemical obesogens is that there are drugs that have a side effect of weight gain, says Bruce Blumberg, PhD, a professor in the departments of developmental and cell biology and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of California in Irvine. He explains, “Certain medications can cause activation of a receptor (called PPAR-gamma) that is the master regulator of fat cell development. Such drugs can cause significant weight gain. And, we’ve found that a chemical called tributyltin (a contaminant in vinyl plastics, some seafood and house dust) activates that same receptor. Our animal studies confirm tributyltin can make mice fat, as compared to animals not exposed to the chemical.”

Tuft’s Rubin has been studying how bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical used in food-can linings, plastic containers and cash register receipts, may affect body composition. “We’ve found that exposing mice to BPA during pregnancy and during the period of nursing can result in higher body fat and weight compared to animals not exposed to BPA during these critical periods,” she says. Rubin has found these effects at levels of BPA exposure that are within the range of what people may encounter in the environment.

However, the Endocrine Society’s recent position paper on obesity notes that not all mice and rat research has shown that exposing animals to BPA during development impacts their growth rate and weight. And, research has been inconsistent as to what amount of BPA exposure has an effect.

Research Limits:

Scientists can’t intentionally give people something in a trial that may be harmful. So, studies on the effects of chemical obesogens in humans are observational; they can’t prove cause and effect. And, similar to animal studies, results from human studies are inconsistent.

For example, observational studies looking at levels of BPA in kids’ urine (a measure of exposure) at a single time point have shown an association between increased BPA in urine and increased obesity risk. But, observational studies that have tracked measures of BPA exposure and kids’ weight over the first few years of life have had mixed results. Some have shown an association between BPA exposure and increased weight, but others haven’t.

Scientists also are trying to determine how exposure to obesogens might affect future generations. “If I treat pregnant mice with a very low dose of tributyltin, their offspring get fatter all the way out to four generations later, compared to non-exposed animals,” Blumberg says. That’s called epigenetic programming and is found despite only exposing the first generation to the chemical. Whether this could happen in people is unknown.

In Perspective:

The Endocrine Society concludes that studies don’t clearly show an increased risk of obesity from exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. But, the group calls for further research into the effects of such chemicals on obesity, among other factors that may increase obesity risk. Also, note that being at increased risk of obesity doesn’t mean a person will become obese. Following a healthy eating pattern, controlling portions and getting regular exercise will help stack the odds in favor of a healthy weight.

To learn more: Reproductive Toxicology, March 2017

To learn more: Endocrine Reviews, August 2017

To learn more: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences – Obesogens

Clear evidence shows that to control your weight:

– Follow a healthy eating pattern:

That includes eating non-starchy vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, vegetable oils, healthful dairy products (such as unsweetened yogurt and milk), fish and other lean proteins. And, limit or avoid fatty and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages and refined grains and starches.

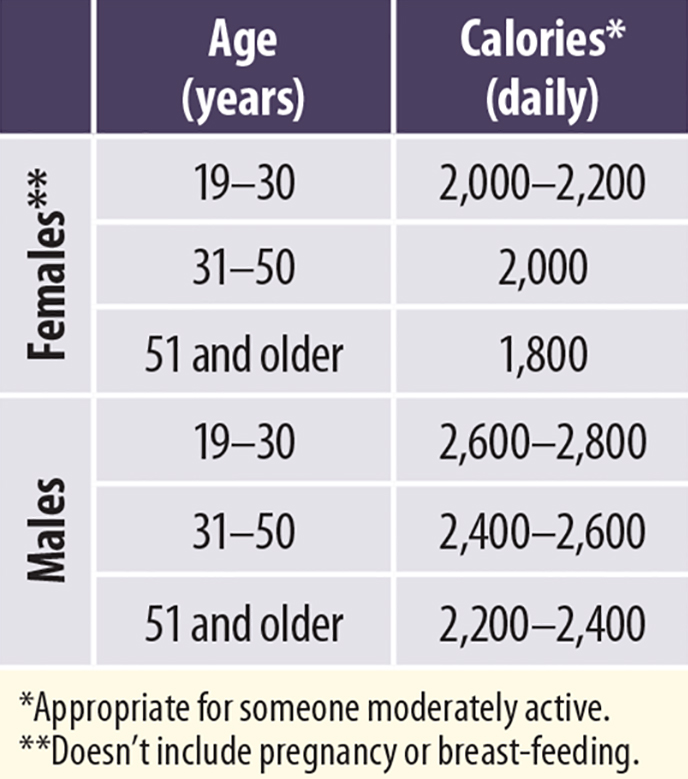

– Maintain an appropriate calorie intake:

Pictured above are some general guidelines, but visit ‘supertracker.usda.gov/bwp’ to personalize this. Although you don’t have to track your daily calorie intake, it’s helpful to know your daily target so you can put calories from food labels, recipes and restaurants into perspective.

– Get regular physical activity:

That includes doing at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or a combination of the two.