In recent years, the internet has been full of articles describing symptoms of “leaky gut syndrome”—and offering diet plans and supplements to treat it. You may be surprised to learn that, while there is some truth behind the concept, this “syndrome” is not a clear, medically recognized, diagnosable disorder. Let’s take a look at the facts and myths behind the hype for this popular complaint.

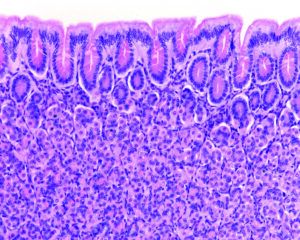

Your Amazing Intestines. Your digestive tract is essentially a tube that runs through your body. It may sound strange, but everything that passes through this tube is actually still outside of your body. The skin is considered the body’s largest organ, but the internal lining of the 25 to 30 feet of human intestine has an even larger interface between your body and the outside world. A single layer of cells lining the small intestines—the epithelium—serves as a gatekeeper, deciding what can be absorbed into the body and what cannot. It is designed to let nutrients in and keep undigested food particles, microbes, and toxins out. To prevent any leakage, these cells are connected by multiprotein complexes called tight junctions.

If something causes these tight junctions to loosen, the barrier becomes more permeable, and unwanted particles may slip through. “Leaky gut” is a popular term for what doctors and scientists call increased intestinal permeability.

In addition to its role in digestion and absorption, your gastrointestinal tract is also a key part of your immune system. About 70 percent of the body’s immune cells are in the area just under the intestinal epithelium, and some immune cells are even embedded in the epithelium itself. This means any bacteria or other unwanted invaders that make it through the first layer of the lining should be met with a swift, strong immune response. Part of any immune response is inflammation, which can have some undesirable effects. “The end result is the potential for an inflammatory response and/or alterations in the gut microbiome, the (mostly beneficial) bacteria and other organisms that live in your gut,” explains Alicia Romano, MS, RD, a clinical dietitian at Tufts Medical Center.

A Gut-Disease Connection? Some of the best data on “leaky” intestines comes from research on celiac disease. In the year 2000, researchers discovered a protein called zonulin in the cells lining the small intestines. When activated, this protein can cause the tight junctions to loosen. In some people, the presence of gluten in the gut (from consuming wheat, rye, or barley products) can activate zonulin. “If an individual is very healthy, has an otherwise strong intestinal barrier, and is not sensitive to gluten, that opening is very transient and no big deal,” says Robin Foroutan, MSD, RDN, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. In people with celiac disease, however, the amount of zonulin produced is much higher, and it stays in the gut much longer, leading to a significant increase in gut permeability.

We do know that increased intestinal permeability is associated with a number of gastrointestinal diseases. “In addition to celiac disease, conditions associated with increased intestinal permeability include Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO),” says Romano. But it is not known if changes to the epithelium contribute to these conditions—or are caused by them. In other words, does “leaky gut” lead to inflammation that triggers Crohn’s disease and other conditions in genetically predisposed individuals, or do these conditions damage the lining of the gut, causing it to leak?

To add to the complexity, the microbes that live in our guts are closely enmeshed in our general health as well as the health and function of our gastrointestinal system. [Editor’s note: The February issue of Tufts Heath & Nutrition Letter will come with a Special Supplement on the microbiome.] There is growing evidence that changes to the composition of the gut microbiota may impact intestinal permeability. Additionally, chronic stress, alcohol use, smoking, medications such as antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), genetics, and environment may also contribute to altered intestinal permeability, whether by changing the composition of the gut microbiota or through other mechanisms.

Image © Jose Luis Calvo Martin & Jose Enrique Garcia-Mauriño Muzquiz | Getty Images

A Weak Link. The little we currently know about increased intestinal permeability has been extended in social media and the popular press to a wide range of disorders and symptoms—without much data. The theory behind “leaky gut syndrome” is that if you have ongoing increased intestinal permeability, the gut’s immune system may trigger cascades of inflammation and this inflammation may cause unpleasant symptoms (such as fatigue, skin rashes, and headaches) as well as contributing to a diverse array of diseases and conditions, from gastrointestinal to cardiovascular, neurological, and metabolic. Many of these conditions are associated with chronic inflammation in the body. While there is a known association between “leaky gut” and intestinal inflammation, the link with chronic, systemic inflammation is as yet unproven.

The fact is, scientists are still trying to understand the complex interactions that lead to “leaky gut,” how to measure it, and, especially, what happens in the body when intestinal permeability does increase. During the past decade, there has been a rise in research exploring possible links between increased intestinal permeability and chronic inflammation in the body, so we should know more in future.

Difficult Diagnosis. One of the reasons research on the effects of “leaky gut” is difficult is that there is no easy or accepted way to measure gut permeability. Doctors have a couple of tests available to them, but studies have shown these can be unreliable.

Gastrointestinal symptoms (like gas, bloating, cramping, floating or tarry stools, constipation, or diarrhea) can have many causes likely unrelated to intestinal permeability. If you suffer from food-related symptoms or unexplained chronic fatigue, headaches, or skin conditions, don’t assume “leaky gut” is to blame. Find a doctor to get a diagnosis. Symptoms like these can arise from a wide variety of illnesses, many of which require medical intervention. If no underlying medical cause is found, careful evaluation using short-term “elimination diets”—where you try taking out and then adding back specific foods—may help untangle the cause of your symptoms. Trying to treat yourself with supplements or dietary changes without the guidance of a healthcare provider can put you at risk for complications.

Diet and Gut Permeability. “Since a number of factors outside of diet may contribute to increased intestinal permeability,” says Romano, “it seems unlikely dietary measures alone will be enough to fix it.” Most of the human studies to date showing that dietary changes or supplements can alter intestinal permeability are small and preliminary. Further research is crucial to understanding the potential role for specific dietary interventions in treating a variety of diseases that could be related to changes in intestinal permeability, but, for most of these diseases, we are not there yet.

Many proponents of “leaky gut syndrome” recommend avoiding specific foods groups, such as wheat products and dairy. “We don’t have enough evidence to suggest cutting out specific food groups will help,” Romano says. Additionally, some conditions associated with increased intestinal permeability, like inflammatory bowel disease, increase risk of nutrient inadequacy, so dietary restriction may do more harm than good. Romano suggests the best course of action is to work with your healthcare provider and/or a registered dietitian nutritionist they recommend to develop a diet personalized to your diagnosis and needs.

Meanwhile, focus on consuming a heathy dietary pattern. “Healthy diets are good for all kinds of chronic conditions,” says Foroutan, “and they are also good for the gut.” Incorporate more fruits and vegetables (fresh, canned, frozen), whole grains (including gluten free whole grains if you have celiac disease), and nuts and seeds (and their butters), and reduce intake of highly processed foods, large amounts of concentrated sweets, and irritants such as alcohol.

Scientists are hard at work unravelling the mysteries of our amazing, complex guts. “We are always gaining more knowledge about how our gastrointestinal system is impacted by diet, lifestyle, and environment, and we can start to apply this knowledge to the treatment and prevention of disease in an increasingly more refined way,” Foroutan says. “This is a really exciting time.”

If you’ve been reading about “leaky gut syndrome” and think it might apply to you, our experts suggest the following tips:

- Know the facts. Increased intestinal permeability is a real thing, but science tying it to all of the symptoms and conditions attributed to so-called “leaky gut syndrome” is still at an early stage.

- Get a diagnosis. Find a healthcare provider experienced in food and nutrition to help you get to the bottom of your symptoms.

- Get good dietary advice. Work with your healthcare provider to develop a diet plan individualized to your diagnosis and personal needs.

- Don’t be fooled. Don’t believe everything you read online about “leaky gut” or claims about dietary changes or supplements to “cure” it.

- Eat a healthy diet. Help keep your gut healthy by consuming plenty of fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts/seeds, whole grains, and yogurt (within the limits of any diagnosed medical issues).

Thank you. Eating a healthful diet and avoiding highly processed foods will help so many major diseases, it will no hurt “leaky gut” or not.

A research team with Zack Bush, MD has experimentally created increased permeability with application of minute amounts of glyphosate, an antibiotic chemical that is everywhere. The science is now showing that over-use of antibiotics of all sources may be a primary factor creating intestinal permeability and compromised immune function. Gut health is directly dependent on a full microbiome. 30% of the species previously found in the gut are missing from the average consumer.