Image © Katarzyna Bialasiewicz | Dreamstime.com

Tufts scientists were the first to coin a term for the gradual loss of muscle mass, strength and function that can occur with aging: sarcopenia. The decline in skeletal muscle from sarcopenia affects 15% of people older than age 65, and 50% of people older than age 80.

Some studies—including those conducted at the Tufts’ HNRCA Nutrition, Exercise Physiology, and Sarcopenia Laboratory—suggest that older adults may be able to stave off muscle loss by consuming more protein than the currently recommended amounts. The body’s ability to manufacture muscle from protein decreases a bit with aging, so increasing dietary protein—in concert with muscle-building exercise—could help to maintain muscle mass and strength.

“Some researchers believe that the recommended amount for older individuals is a little low—that it probably should be higher,” says Donato A. Rivas, PhD, a scientist at the Sarcopenia Laboratory.

It’s been less clear what impact that preserving muscle health has on general quality of life, and a recent study in the British Journal of Nutrition tries to address this question. Though its findings come with some important limitations, the study helps to fill the science gap, says the study authors: “This finding adds to the growing body of evidence to support the health and well-being benefits of increasing high-quality dietary protein intake in older adults and the elderly, particularly in combination with exercise.”

Protein and Muscle: The researchers drew on the findings of a previous clinical trial that they reported in 2014 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. For that 4-month study, 100 women aged 60 to 90 were recruited, all relatively healthy and living in retirement communities in Melbourne, Australia. The women agreed to attend twice-weekly progressive resistance-training classes to build upper and lower body strength, balance and flexibility.

The women were randomly assigned to one of two diets. In the “protein-enhanced” group, the women were asked to eat about 3 ounces of lean, cooked meat (beef, veal, or lamb), at both lunch and dinner, 6 days a week. (A 3 ounce serving of meat is about the size of a deck of cards.) Two servings of red meat a day is substantially above the amount recommended for Americans by the Institute of Medicine, but not much higher than what the average American is eating today.

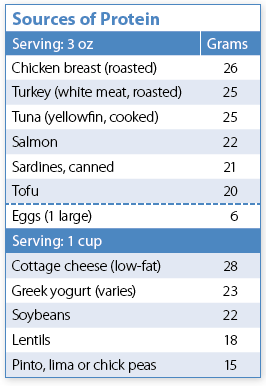

For the purpose of the study, the meat provided a way to temporarily boost protein intake for 4 months. Ordinarily it’s better to obtain your protein from a variety of sources, including plants, since red meat is associated with some health risks.

Women in a comparison group were told to have larger servings of breads, cereals and vegetables, and smaller servings of protein-rich foods. The carb-heavy diet group consumed an average of 80 grams (for a 150-pound woman), compared to 90 in the protein-enhanced group.

Despite the modest difference, the protein-enhanced group gained more lean muscle mass (about a pound) compared with the women on the lower-protein diet. Leg strength in the enhanced-protein group was 18% greater.

Quality of Life: But would the improved muscle mass and function offer any benefits in terms of overall quality of life? To get some clues, the researchers revisited their earlier study findings. The women had filled out a detailed questionnaire at the beginning and end of the earlier study that measured “health-related quality of life.” It included questions about their overall ability to perform typical daily activities such as walking, climbing stairs, and working. The study also assessed their general sense of vitality and well-being.

The study found that those in the higher protein group maintained (and in some cases even slightly improved) their quality of life, particularly in physical aspects of their lives, such as physical functioning and bodily pain.

What does it mean for you? The quality-of-life aspect of the study was a short-term reanalysis of data from a previous study that was not originally designed to measure quality of life. As a result, the findings can’t be used to draw a direct link between muscle health and quality of life. “It’s hard to make a conclusion based on just having somebody go through that for four months,” Donato notes.

While science sorts out the optimal mix or amount of protein and exercise needed to help older adults to live an active, independent lifestyle, there is some pretty strong evidence that adequate protein intake and regular resistance training are the cornerstones of muscle health.