If you studied the headlines this spring about the latest report on dietary sodium and concluded you could stop worrying and maybe have an extra bag of chips, think again. True, thats certainly how most of the news coverage of the report from the prestigious Institute of Medicine (IOM) read: No Benefit Seen in Sharp Limits on Salt in Diet, headlined the New York Times. Report questions reducing salt intake too dramatically was the take in USA Today. And CNN announced, Report questions benefits of salt reduction.

People at my book club were asking, Did you see that study about how we dont have to worry about salt anymore?, says Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, director of Tufts HNRCA Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory. They didnt know I was on the committee!

>From the inside of the expert panel, commissioned by the IOM at the behest of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the take-away was very different. The IOM specifically asked us to look at the relationship between sodium intake and health outcomes, not to make recommendations for daily sodium intake, Lichtenstein explains. The bottom line is there is good data to indicate reducing sodium intake to 2,300 milligrams per day and even 1,500 per day will decrease blood pressure, an intermediate marker of risk.

With regard to cardiovascular disease, a health outcome, there is good data to indicate reducing sodium intake to 2,300 milligrams per day is beneficial; there is virtually no data on further reductions to 1,500 milligrams per day, Lichtenstein goes on. That does not mean there is no benefit-most likely there would be-but we cannot be certain in the absence of data.

ASSAULTED BY SALT: In any case, most Americans have a long way to go to reach the more thoroughly studied target of no more than 2,300 milligrams daily. The current average sodium intake is 3,400 milligrams daily-about the amount in a teaspoon and a half of salt. But most of our sodium consumption comes not by the spoonful but in less obvious forms. According to the American Heart Association,up to 75% of the sodium in the average American diet derives from salt added to processed or restaurant food.

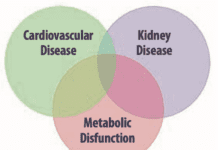

The Heart Association, which advises a maximum 1,500 milligrams daily of sodium for everyone, quickly responded to the IOM report, saying, We had these data that the IOM reviewed available to us, and we did not change our recommendation. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended limiting sodium to less than 2,300 milligrams a day, but set a lower, 1,500-milligram target for ages 51 or older, African-Americans, and those with high blood pressure, diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Nonetheless, more than 95% of Americans over age 50 consume more than 1,500 milligrams of sodium daily.

ADVERSE EVENTS?: The other part of the IOM report that sparked misleading headlines was a finding that patients with advanced heart disease who cut down on sodium might actually be at greater risk of adverse events. But this applied only to people with mid- to late-stage heart failure receiving an aggressive treatment for their disease not used in the US. Other data on downsides of low-sodium diets, the report concluded, were insufficient and inconsistent. The news media pounced on the potential adverse effects, says Lichtenstein. But we really dont have good-quality data to draw this conclusion. In fact, we could not rule out the possibility that those people reporting the lowest sodium intakes were the sickest, sometimes referred to as reverse causality.

WHAT TO DO NOW: Further research is needed, the IOM report concluded, to shed more light on associations between lower levels of sodium (in the 1,500 to 2,300 milligrams per day range) and health outcomes, both in the general population and subgroups. Recent studies, it noted, suggest that dietary sodium intake may affect heart disease risk through pathways in addition to blood pressure.

In the meantime, Lichtenstein says, the best advice continues to be to work to limit your sodium intake, because current levels are clearly too high. Thats becoming easier, she adds: More reduced-sodium foods are available now, and more companies are quietly figuring out how to reduce the sodium content of food within there being much of a difference in taste. In all cases, as more people choose lower sodium foods, that trend will continue.

Cooking more of your own food and relying less on processed, packaged and other commercially prepared foods is another key strategy, she says. To save time, cook multiple healthy meals at once and freeze the extra or use for lunch the next day.